At the beginning of the year 1869, Asa Moore Janney (1802-1877) was a miller living near Lincoln, Loudoun County, Virginia, with his wife Lydia and two adult daughters. The Janneys had spent their lives as Quakers following the principles of that faith, including anti-slavery, pacifism, and tolerance. Asa and his family had survived the violent years of Civil War, much of it fought on the fields of their native state. Their own mill had been burned by Union troops in the autumn of 1864, to great financial loss. By 1869 Asa was 67 years old, his wife Lydia was 66, and their children grown adults. Asa and Lydia could have led quiet, peaceful lives in their little village.

This pastoral, familiar life was upended when Asa agreed to become Indian agent on the Santee Sioux Reservation in Nebraska. He served in this position for two years, 1869-1871. Asa’s older brother, Samuel M. Janney, served during those same years in Omaha as Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the state of Nebraska. More information about Samuel Janney, and the experience of both Janney brothers, can be found in the post “Grandfather” of an Indian nations, 1869-1871.

President Ulysses Grant initiated a Bureau of Indian Affairs “Peace Policy” in 1869. A good, simple explanation of the Peace Policy written by Jennifer Graber can be found here. Grant was attempting to rectify years of the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ corruption and ineptitude. Under his new policy, he turned to religious leaders, including Quakers, to fill Indian reservation jobs of Indian Agents and Supervisors. The Society of Friends (Quakers) had long included efforts within their religious practice to help America’s native population. They sent clothes, school books and money to Indian missions, and Quaker leaders visited reservations. In many respects, the Quaker efforts toward native Americans mirrored their actions for the nation’s black population.

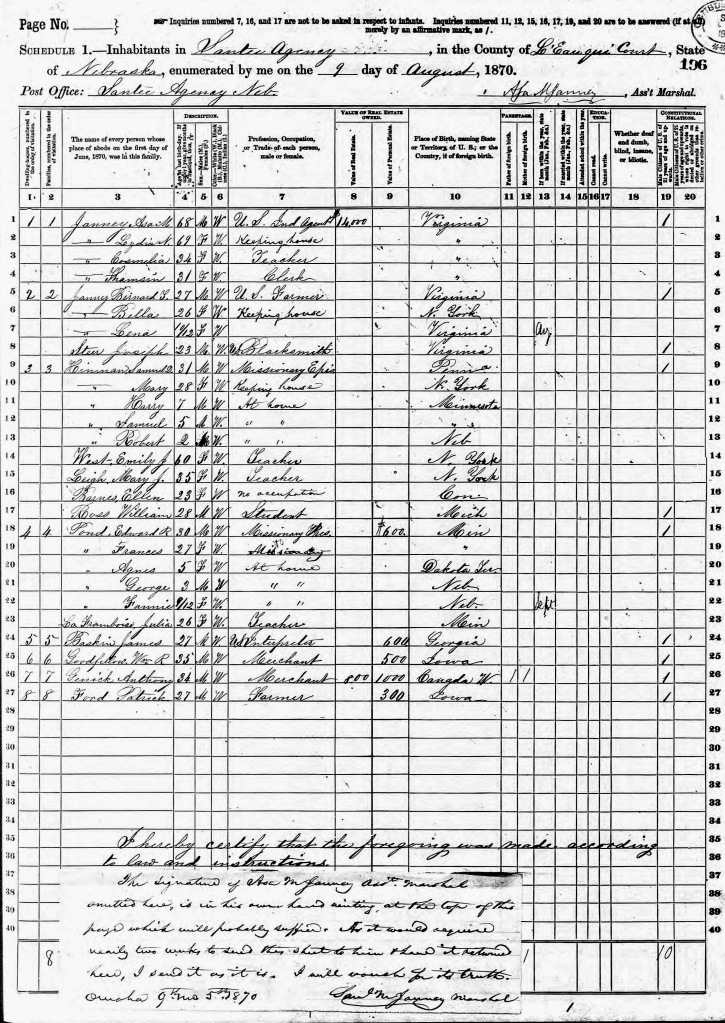

From this religious background, yet having no special expertise – other than a willingness to be fair and honest – Asa Moore Janney went to the Santee Sioux reservation along with wife Lydia, and daughers Cosmelia and Thamsin. An 1870 U.S. Census for “Inhabitants in Santee Agency” shows the Janneys (at the top of the page) as well as other white residents of the reservation, some of them Quakers. Asa’s brother, Samuel M. Janney, designated himself “Marshall” and signed at the bottom of the census page, vouching that the information on the form was correct: “The signature of Asa Moore Janney Ass’t. Marshall ommited here, is in his own hand writing, at the top of this page, which will probably suffer. As it would require easily two weeks to send this sheet to him and have it returned here, I send it as it is. I will vouch for its truth. Omaha 9 m0 5th Saml M Janney Marshal

It was a tumultous time for the Sioux nation, a people feared and fought but rarely (if ever) understood. A thorough study of the history of the Sioux tribe associated with the Quaker mill owner, Asa Moore Janney, is found in Roy Meyer’s History of the Santee Sioux, published in 1967, with a revised 1993 edition.

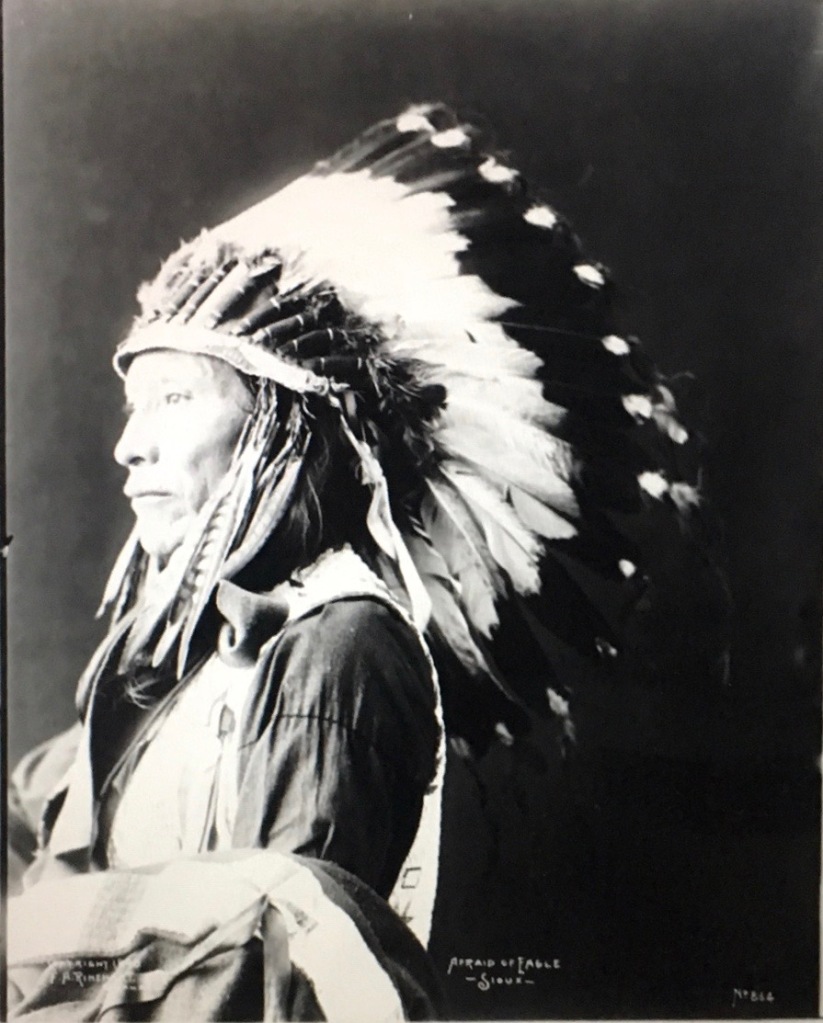

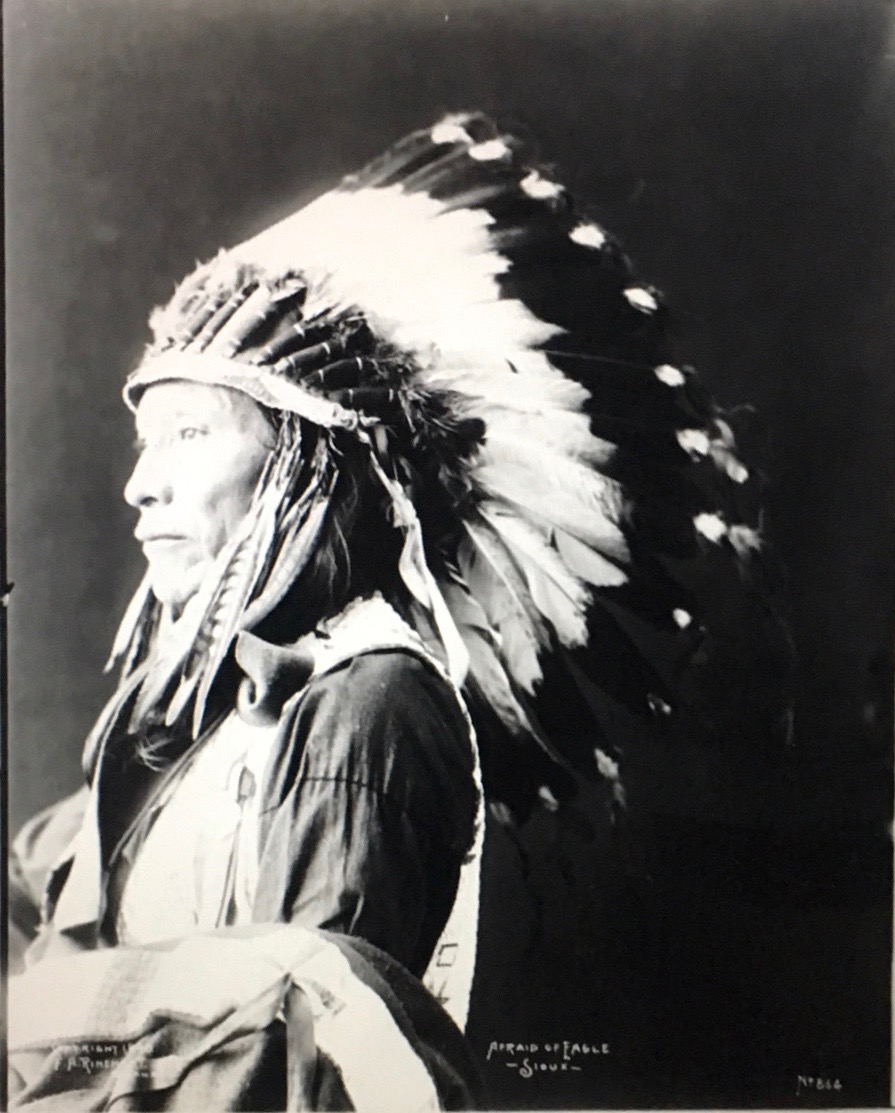

In History of the Santee Sioux, Roy Meyer gives details of both Indian Agent Asa M. Janney’s and Supervisor Samuel M. Janney’s two years in Nebraska. The following excerpts from the book show some of the extraordinarily complex culture with which the Janneys and their colleagues had virtually no experience. Asterisks are used following some excerpted paragraphs, with notations of sources. The photos interpersed in the text are added by myself, showing Santee Sioux Indians, reservation landscape, land allottment documents and maps.

History of the Santee Sioux excerpts:

Pp. 163 – 167 Though parts of the Santee Reservation, especially the wild, rugged area called the Devil’s Nest, possess a certain austere beauty, agriculturally it was no substitute for the rich lands of the Minnesota valley taken from the Indians by Congress in 1863.

The year 1869 brought other changes to the Santee Sioux. As part of President Grant’s revamping of Indian policy, the Northern Superintendency was turned over to the Society of Friends. Samuel M. Janney replaced Denman as superintendent, and his brother, Asa M. Janney, was appointed Santee agent. The Janneys, natives of Loudoun County, Virginia, were both in their late sixties when they came to Nebraska and were lifelong members of the Society. Samuel, the elder by two years, was the author of at least ten books and pamphlets, including some poetry on Indian themes. He had at one time operated a girls’ boarding school in Virginia and had interested himself in Negro education before the Civil War. The two men were full of ideas about the management of the agency, ideas which, for better or worse, continued to affect the Santee Sioux long after the Janneys had left office. *

*Notes: Com. Of Indian Affairs, Annual Report, 1868, p. 5; Henry E. Fritz, The Movement for Indian Assimilation, 1860-1890 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1963), pp. 73-74; William Bacon Evans, “Dictionary of (American) Quaker Biography,” ms in Quaker Collection, Haverford College

One of the pet schemes nursed by Agent [Asa] Janney, who had been a miller in his home state, was to build a gristmill on Bazile Creek, move the agency there, and establish the Indians on farms surrounding this administrative center. There was no flour mill within forty miles, and it was thought that a considerable saving could be made by grinding the wheat raised by the Indians rather than shipping in flour, as had been done in the past. Shortly after he took office, Janney began drawing up specifications for a mill, and construction got under way in 1870. After several delays, the mill was finally ready to start grinding in June, 1871. No sooner had it begun operating, however, than portions of the dam gave way because of the porous nature of the soil. Such accidents continued to interrupt milling activities throughout the years the mill was in operation. A fine three-story chalkstone structure, it speedily became a liability rather than an asset to the agency and eventually had to be abandoned. *

*Notes: S.M. Janney to [Ely S.] Parker, August 20, 1869, and June 17, 1870; Asa M. Janney to S.M. Janney, September 17, 1869, January 10, June 27, and November 12, 1870, NARS, RG 75, LR; A. M. Janney to S.M. Janney, June 4 and 21, 1871, NARS, RG 75, LR, Santee Sioux Agency; Com. Of Indian Affairs, Annual Reports, 1883, p.108.

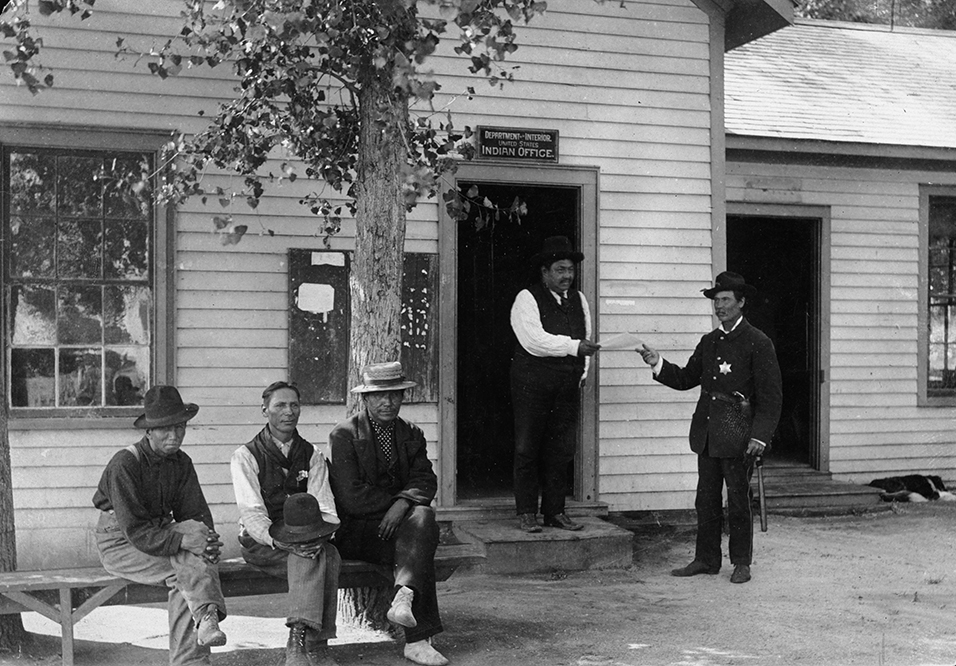

[Asa] Janney’s hopes for moving the agency to Bazile Creek were never realized, but another project of his, an Indian police force, did become a reality. The idea originated when the chiefs refused to take action against one Mazazidan, who was charged with a busing his wife and stealing horses. Janney and his employees were finally obliged to arrest Mazazidan themselves, but the agent thought it would be better to have a corps of men, carefully selected for reliability, who would be responsible to the agent for the maintenance of law and order. In October, 1869 he asked for, and shortly received, authority to organize a police force to consisted of one man from each of the six bands, chosen by the chiefs. At first he tried paying them on a fee basis, so much for each arrest, but he found them overzealous and had to abandon that policy in favor of a flat wage of five dollars a month. Except for a few intervals, the police force, one of the first such experiments on any reservation, remained a permanent institution at Santee for the rest of the nineteenth century. *

*Notes: A. M. Janney to S. M. Janney, October 19, 1869, and January 22, 1870, NARS, RG 75, LR.

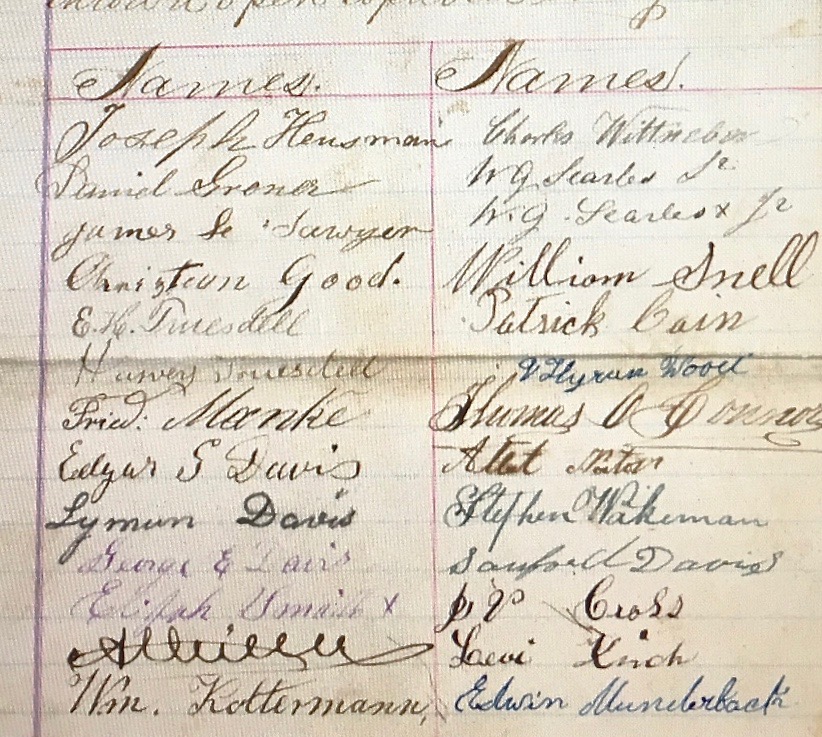

[Asa] Janney’s most important achievement during his two years as agent was the allotment of land to the Indians and their settlement on farms scattered over the reservation. The uncertainty of their tenure led some of the more thoughtful to the conviction that their only security lay in the allotment of land in severalty. Fearing that nothing would be done toward this end at Santee, and resenting the authority of the old chiefs, a number of the men who had emancipated themselves from tribalism with their families, and took up homesteads in the valley of the Big Sioux River, in the vicinity of the later town of Flandreau, South Dakota. To forestall similar action by others, Janney began to press strongly for allotment almost as soon as he became agent. He called the Indians together in the summer to tell them of his plans and to get their reaction. He was able to report a favorable response, and sent to Commissioner Ely S. Parker a petition from the chiefs and headmen asking for allotment as a means of preventing a further exodus by men who believed “that the Government does not intend to give them here a permanent home.” *

*Notes: A. M. Janney to S. M. Janney, June 19, 1869; Chiefs and Head Men to Commissioner Parker, July 19, 1869, ibid.

Although Janney’s first intention was to allot 160 acres to each of two hundred heads of families, under the terms of the 1868 treaty. He later adopted the plan of allotting smaller farms of 40 and 80 acres, as specified in the act of March 3, 1863. He proposed to spend $329 per family, this sum to cover a house (for fifty dollars), a yoke of oxen, a stove, a cow, six sheep, two goats, and two hogs. It would be best, he thought, to settle the valleys first, since they contained the land best suited for the Indians and also because there was a threat of a land grant to a railroad that would follow the course of Bazile Creek. *

*Notes: A. M. Janney to S. M. Janney, October 1, 1869, and January 10, 1870; S. M. Janney to Parker, January 3, May 31, and June 17, 1870, ibid.

As with his other projects, the allotment did not proceed quite as Janney wished. There were delays in the survey, and the agent was faced with knotty problems such as how much land to give a man with more than one wife. By the end of May, 1870, however, two hundred farms of 80 acres and two hundred of forty acres had been laid out. Some Indians had already settled on their farms then, and by the next spring about sixty families were thus located, despite a drought the previous year which had resulted in an almost complete crop failure. *

*Notes: S.M. Janney to Parker, February 8, March 11, and May 31, 1870, ibid.; S.M. Janney to Parker, February 21, 1871; A. M. Janney to S.M. Janney, May 1 and July 5, 1871, NARS, RG 75, Santee Agency; Com of Indian Affairs, Annual Report, 1870, p. 227.

In his last annual report, made in July, 1871, Janney wrote that about 80 houses had been built on individual allotments and furnished with windows and doors from a sawmill which he had set up two years earlier. Most of the houses had tables, often covered with oil cloth, bedsteads, cupboards, and benches or seats were common now. Over 150 bed quilts had been made in the previous eighteen months. Some women were raising chickens, and nearly half the families had cows. *

*Notes: Com. Of Indian Affairs, Annual Report, 1871, pp. 441-443

It should perhaps be mentioned that the Indians did not receive patents for these allotments. Instead, they were given certificates which stated that the United States would hold the title in trust for the holder and his heirs so long as they continued to occupy the land. It was specified that these certificates conferred no right except that of possession; further legislation by Congress would be required to convey a fee simple title.*

*Note: Sample certificate (no date), NARS, RG 75, LR, Santee Agency.

The decade of the 1870’s witness a gradual decline in the numbers of the Santees. From 974 in 1870, the population dwindled to 791 four years later and to 736 by 1879.*

*Notes: A. M. Janney to S. M. Janney, August 20, 1870, NARS, RG 75, LR; Com. Of Indian Affairs, Annual Report, 1874, p. 36; 1879, p. 236.

The most important single event among many that conspired to bring about this decline was a devastating smallpox epidemic in 1873. About the middle of August a Santee prostitute returned from Fort Randall with a case of what the agency physician diagnosed as syphilis. A scattering of other cases appeared in following weeks, but not until September 25 was the disease recognized as smallpox. By that time it was out of control and the physician himself was down with it. In response to an appeal from the agent, Joseph Webster, the Indian Office sent a special agent to take over and employed a Yankton physician, who hurriedly erected a crude hospital and vaccinated everyone he could. By mid-December the epidemic had run its course, after causing at least 70 deaths out of 150 cases. The effects of the outbreak were similar to those accompanying the great plagues of the past. People fled their homes and camped in isolated places, or else turned the sick out of doors and left them to die in the bushes. Many fled the reservation entirely and never returned.*

*Notes: Dr. George Roberts to Commissioner Edward P. Smith, November 6, 1873; White to E.P. Smith, December 22, 1873, NARS, RG 75, LR, Santee Agency.

Thus the Santee population was considerably reduced both through the deaths themselves and through the panic-stricken flight of many who did not catch the disease.

Despite this outbreak and repeated crop failures, which also caused many departures from the reservation, the population did not diminish fast enough to suit the white population, now filling up the surrounding country. In 1871 a Niobrara merchant wrote Senator P.W. Hitchcock demanding the restoration to the market of the Santee Reservation. “The Counties below are pretty well settled up,” he wrote, “most of the good Land that is not occupied by settlers is in the hands of speculators, the emigration to our County has been good this year and I think next year all the Land will be taken by actual settlers and if you will be kind enough to get those Santee Indians out of Nebraska, the emigration will be much larger yet.” He claimed, with some exaggeration, that the reservation constituted the best part of the county. *

*Notes: H. Westermann to Senator P.W, Hitchcock, November 3, 1871, ibid. Westermann was later said to be a contender for the post of Santee agent, to the dismay of the Indians, who got up a petition protesting against his appointment, on grounds that he was a drunkard, “a man who defies Got,” and an Indian-hater. “For ten years he has been working to drive off the Santee people from this land,” said the petition. See Petition to Commissioner Hiram Price, March 14, 1882, ibid.

When the town of Niobrara acquired a newspaper, it served as a medium of expression for those who wished to have the Indians removed. Edwin A. Fry, the spitfire editor of the Niobrara Pioneer, argued that the Indians were kept there in order to furnish jobs for the agency employees, who “generally see that their red charge get paid for loafing.” *

*Notes: Niobrara (Nebraska) Pioneer, October 20, 1874

Pp. 171-172 All the Santee agents during the 1870’s were Quakers, apparently hard-working, conscientious men, at least in so far as their correspondence and the absence of evidence to the contrary can furnish a key to their character.

Another reason for the lack of continuity on the reservation was the vulnerability of the Indian Office itself, which was politically controlled and had to respond to the same pressures as other government agencies. The panic of 1873 brought a general retrenchment that was bound to affect the Santee agency in time. Agent Searing complained in 1876 that the “sweeping reduction in the employee force” had produced unfortunate effects at Santee. There was no money to pay the police force, for example, and their services, which had become quite valuable, had had to be dispensed with. During that summer the gristmill was idle and the various shops closed mos of the time owing to a lack of men to operate them.*

*Notes: Com. Of Indian Affaires, Annual Report, 1878, p. 100

[Asa] Janney’s white elephant, the gristmill, was a source of much annoyance and may have played a role in delaying the agricultural progress of the Santees. At times when it was idle due to low water or a washout at the dam, the agent had to contract for flour at a price much higher than that charged for wheat. About the most that could be said for the mill was that the constant need for repairs provided employment for a number of Indians and thus enabled them to collect rations. *

*Notes: Edw. C. Kemble, U.S. Indian Inspector, to J.Q. Smith, January 22, 1877, NARS RG 75, Nebraska Agencies.

Pg. 297 Any discussion of the history of these [Sioux] groups in the twentieth century is bound to be sketchy, and any judgments rendered are inevitably inconclusive, since not all the returns are yet in. Even Santee, whose history a superficial observer might think finished, still retains much of its identity as an Indian community after more than seventy-five years of attempted assimilation, and probably will continue to do so for some time to come. Yet its history for the first thirty years of the century was judging from their official reports, the men placed in charge there lacked the evangelical zeal displayed by such men as Janney and Lightner in the 1870’s.

Both Asa M. Janney and his brother Samuel M. Janney left their Indian bureau posts in 1871, earlier than the three year appointment ended. Their experiences in Nebraska, by any objective account, contained disappointment. As Quaker historian Clyde Milner II put it in his 1982 book, With Good Intentions, (University of Nebraska Press):

“…no other group of white Americans in the post-Civil War period could have prevented the rapid decline of these native people into abject poverty and social displacement. Sadly, the example of the Quaker Indian agents indicates how the desire to do good does not always produce beneficial results. By the 1870s, well-meaning white friends could not solve the complex issues which confronted the [Nebraska reservation tribes]. Tragically, these Indians found that they had lost control of their own fate as well.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cosmelia Janney, Asa’s daughter, and Eliza Janney, Samuel’s daughter-in-law, stayed on to work as Santee Sioux teachers and Indian Bureau office staff for awhile after their family members left Nebraska in 1871. Other Quakers – none from Lincoln, Virginia – continued to participate in the Bureau of Indian Affairs thru the 1870s. Nothing could change the dismal trajectory, however, and the Indian Bureau stopped its policy of hiring religiously affiliated agents and supervisors. Military intervention dominated diplomacy, with predictable results. President Grant’s “Peace Policy” ended in failure.

0 comments on “Asa M. Janney, from Virginia miller to Indian Agent”