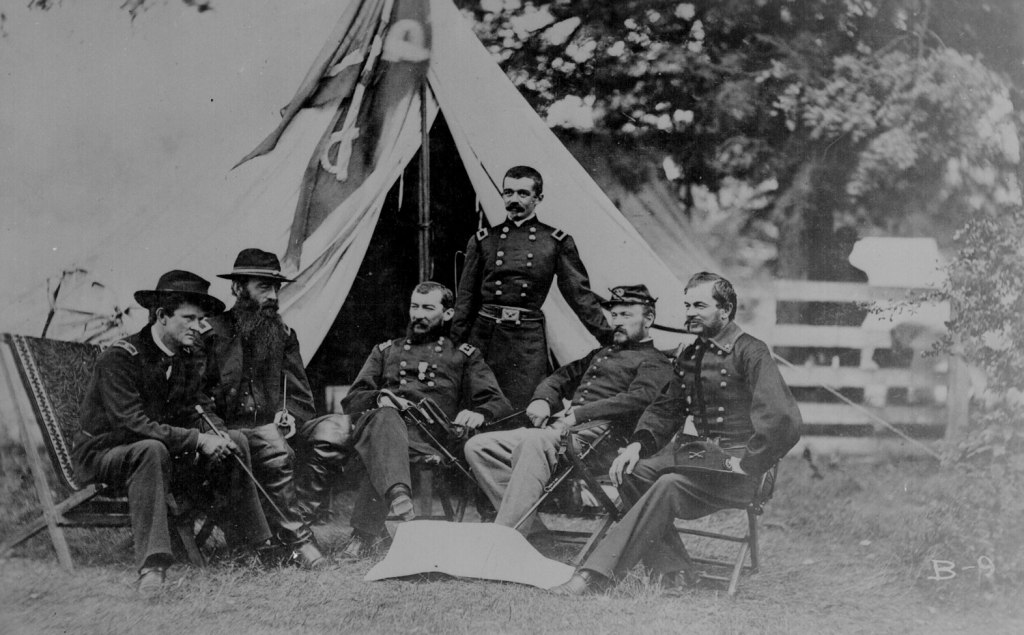

This picture was taken in Virginia 1864; are Gen. Philip Sheridan and his officers mapping out the Burning Raid? Left to right: Wesley Merritt, David McM.Gregg, Sheridan, Henry E. Davies (standing), James H. Wilson, and Alfred Torbert. These officers swept through Shenandoah Valley, including Loudoun County, leaving a trail of burned property. Courtesy of National Archives (#524427)

By the autumn of 1864 the Civil War was drawing to its bloody close. However, Confederate Colonel John Singleton Mosby’s 43rd Battalion was still bedeviling Union regiments sweeping through northern Virginia. Lieutenant General Ullysses S. Grant, Commander of the United States Army, wrote to Maj. General Philip Sheridan:

“CITY POINT, Va., Nov. 9, 1864.

“MAJOR-GENERAL SHERIDAN, Cedar Creek, Va.:

“Do you not think it advisable to notify all citizens living east of the Blue Ridge to move out north of the Potomac all their stock, grain, and provisions of every description? There is no doubt about the necessity of clearing out that country so that it will not support Mosby’s gang. And the question is whether it is not better that the people should save what they can. So long as the war lasts they must be prevented from raising another crop, both there and as high up the valley as we can control.

“U. S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General.”

In August 1864, Grant had ordered his notorious “Burning Raid”, in which citizens in the Shenandoah Valley, including Union supporting Quakers of Loudoun County, would have their barns, mills and crops destroyed and livestock driven away. The Confederate army relied on forage and food supplies from these rich farm fields of the Shenandoah Valley. More information on the Burning Raid can be found here.

Grant followed up his “Burning Raid” order with the Nov. 9, 1864 war memo shown above; he seemed to want Valley farmers to have the opportunity to take moveable property north, out of the path of the coming destruction. (I’ve never seen any record showing how this possible remediation was implimented, if at all.) Grant was still determined to destroy Confederate army supply lines and thereby hasten the end of the war. That meant the destruction of civilian property, wiping out everything except the roof over each farmer’s head.

In his Personal Memoirs, written in 1888, Major General Philip Sheridan (1831-1888) analyzes the “Burning Raid” strategy instigated by Union Army Commander Grant. Sheridan writes in Memoirs Chapter 24, Volumn 2, about the necessity of that policy, making the following insight:

“…I endorsed Grant’s programme, for I do not hold war to mean simply that lines of men shall engage each other in battle, and material interests be ignored. This is but a duel, in which one combatant seeks the other’s life; war means much more, and is far worse than this. Those who rest at home in peace and plenty see but little of the horrors attending such a duel, and even grow indifferent to them as the struggle goes on, contenting themselves with encouraging all who are able-bodied to enlist in the cause, to fill up the shattered ranks as death thins them. It is another matter, however, when deprivation and suffering are brought to their own doors. Then the case appears much graver, for the loss of property weighs heavy with the most of mankind; heavier often, than the sacrifices made on the field of battle. Death is popularly considered the maximum of punishment in war, but it is not; reduction to poverty brings prayers for peace more surely and more quickly than does the destruction of human life, as the selfishness of man has demonstrated in more than one great conflict.” (Emphasis mine.)

Loudoun Quakers had to be philosophical about the Union army’s destruction of their property. Several accounts found on Nest of Abolitionists, including those written by Lydia Janney Brown and Carolyn Taylor, told of the Federal “Burning Raid.” Maj. General Sheridan was correct to note that “the loss of property weighs heavy” with citizens caught up in war, but it was a loss most Quakers in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia were willing to bear if it meant ultimate victory for the United States. Plus, if their Confederate neighbors’ property was destroyed but their own barns and mills and crops spared, how could they ever hope to rebuild cultural and social ties with fellow Virginians?

0 comments on “General Philip Sheridan explains how to end a War.”