Francis H. Ray (1835-1862) was born into a prosperous Quaker family in Rayville, New York. He was a prominent figure in the controversial March 15, 1856 Goose Creek Literary Society Meeting, of which a page of “Nest of Abolitionists” is devoted. I think young Francis deserves a page of his own. For more information on him, read the Goose Creek “Black Republican” Literary Society page on this website.

I have been able to find no pictures of Francis – hopefully someone has a picture they will be able to share. Elizabeth Grace of Old Chatham, New York, sent information about the Ray family, including these likenesses of Francis Ray’s parents, David and Lydia Ray:

The Rays were a family of merchants and lived in a town named Rayville, founded by Francis’ grandfather. The Rays had a home that reflected their status in the community. An illustration of the Ray property and the surrounding countryside was published in the Chatham Press, Columbia County, NY, June 2010:

In 1855 at the age of 20, Francis left Rayville and his comfortable upbringing to come to teach at Springdale School in Lincoln, Virginia. Springdale had been opened in 1832 by Samuel and Elizabeth Janney as a girls’ non-denominational boarding school, but by 1855 Springdale was owned by Baltimore Yearly Meeting, and run as a Society of Friends co-educational school.

Francis was a young and perhaps idealistic abolitionist, and was bold about expressing his anti-slavery opinions while living in the state of Virginia. A meeting of the Goose Creek Literary Society on April 1856 resulted in a storm of controversy, and forced Francis Ray to slip out of Virginia in the middle of the night, after threats on his life. The episode is covered in detail by Ray’s own article, published in a New York newspaper and picked up by William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator from May 16, 1856 (transcription below):

The Liberator Boston Friday May 16, 1856

From the New York Evening Post.

TO THE PUBLIC.

A SCHOOL-TEACHER EXPELLED FROM VIRGINIA FOR DEFENDING THE PRINCIPLES OF WASHINGTON AND JEFFERSON

CARD FROM FRANCIS H. RAY.

Much has been said of late in the columns of newspapers – particularly those whose advocacy of the ‘peculiar institution’ and devotion to its interests have secured for them prominent positions among the organs of the falsely-styled democracy – respecting a recent gathering in Loudon [sic] county, Va., which, with characteristic magnanimity, they have been pleased to honor with the title of ‘a Black Republican Meeting.’ As one who participated in the proceedings of that meeting, and is well acquainted with all the circumstances connected therewith, I desire to lay before th public the following statement concerning it. And I would here remark, that but for the prominence which these journals have seen fit to give it, and the emphasis with which they have dwelt upon it and the consequent excitement at the South, this meeting was no more deserving of public notice than any of the weekly gatherings of the debating societies which exist in nearly every school district throughout the free States.

About forty-five miles northwest of Washington, in the county of Loudon [sic], Virginia, there has existed for five years a literary society (I am informed the only one in the county) – with the very laudable object – according to the preamble to it’s constitution, of ‘a free exchange of sentiment, the spreading of truth and mutual improvement’ – and the rather uninviting name of the ‘Goose Creek Literary Society.’

The 15th of March last was the day appointed for the discussion by this society of the question:

‘Resolved. That we do endorse the nomination of Millard Fillmore by the American party.’

At a previous meeting, Jesse H. Brown and I were chosen to speak upon the negative of this resolution. The appointed day and hour arrived, and found a respectable number assembled. Among the rest, one James H. Trayhern, a lawyer from Berryville, Clarke county, and the editor of the Democratic Mirror, of Leesburg, Loudon county. When my time to speak arrived, I expressed sentiments strongly opposed to Millard Fillmore, upon the ground that he was an avowed supporter of Southern measures – the signer of the odious and unconstitutional Fugitive Slave Law, & c.; and also opposed the further extension of slavery over territory which, by the united voice of both North and South, had been consecrated forever to freedom, a measure to which it was admitted he was favorable by those upon the opposite side of the question. I said explicitly that I would not meddle with the institution of slavery where it already exists, but would leave it to die out upon the land that bred it. With Washington and Jefferson, and Franklin and Jay, I looked upon slavery as a sectional rather than a national institution, and considered its further extension imimical [sic] and dangerous to the freedom of the people of the United States and the progress of free institutions. J. H. Brown expressed similar sentiments, and concluded by the expression of the hope that the fertile plains and green valleys of Kansas and Nebraska might not, in the language of the Senator from Alabama, (Mr. Clay,) exhibit the painful signs of sterility and decay apparent in Virginia and the Carolinas.

After the four chosen polemics had spoken, and after several brief speeches from others, pro and con, J. F. Trayhern was called upon for a speech in the affirmative of the above resolution. He commenced by regretting that the discussion had turned upon the question of slavery extension, and that any Southern State should be the theatre of so disgraceful a scene; and continued for an hour and a half in delineating what he termed the aggressions of the North and the sufferance of the South, from the time of the formation of the federal Constitution to the present, and in denunciation of Abolitionism and Black Republicanism as the most dangerous enemies of a republican government. He was strongly opposed to the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, and yet, dearly as he loved the Union, he would see it dissolved rather than see that Compromise restored. This sentiment gave rise to some hissing and much excitement. After this truly singular and contradictory statement, he declared – as the conclusion to a lengthy speech, devoted almost wholly to the question of slavery – that I, coming as I did from New York, should not be allowed freedom of speech upon that question upon Southern soil. At this point cried of ‘He has the right’ – ‘He shall have the freedom of speech’ – came from all parts of the room; and I here assured him, that if he would go to New York, I would warrant him entire freedom of speech upon that or any subject. To this I received the response: ‘You can have entire freedom of speech upon Virginia soil, if you will speak right’ – (i.e., as Virginians desire.) Then followed a pathetic appeal in behalf of (not free, but) slave Kansas. He hoped to God slavery would go into Kansas, freedom had already found too much room in these United States; it was the duty, the solemn duty, of every Southern man to aid in establishing it there, the interests of Missouri and the whole South required it; the fidelity which we entertain for the institutions of our fatherland demand it of us.

Throughout this speech might have been witnessed a scene peculiarly pleasing to those who believe the present hostility existing between the American and Democratic parties is intended for anything but political effect. At the side of this Southern advocate of th claims of Fillmore, (in addition to a half dozen pages of notes,) was to be seen the above mentioned editor prompting his American enemy (!) in every emergency throughout his protracted speech. (For a parallel and precedent, vide final vote for Speaker in the House of Representatives.)

After he had concluded, Jesse Hoge addressed the meeting, bearing particularly upon the disunion and anti-freedom-of-speech sentiments of the last speaker. He had heard of Northern fanaticism, through the Southern papers, all his life, but never of any that would compare with that; it was the rankest Southern fanaticism.

Others followed, who had spoken upon the affirmative, declaring that they could never endorse such sentiments as Trayhern had advanced; that they were un-American, and unfit to be publicly proclaimed.

At this point, during the clamor and confusion consequent to his own speech, James F. Trayhern retired, followed by his enemy (!) the editor referred to, and a number of slaveholding sympathizers who had found their way to the meeting.

Now for the sequel. In due time the Democratic Mirror of Leesburg appeared, with a two-column editorial upon this meeting, under the very attractive caption of ‘Black Republican meeting in Loudon.’

Here was an interesting, if not lamentable, exhition [sic] of the far-famed Southern chivalry. At first the editor’s cheek would seem to have blushed with very shame for the tarnished reputation of his country, but his heart was gradually warmed by the fires of patriotism, and his blush gave way to the heat and ardor of battle. We quote his concluding pledge: –

‘We are aware that we have performed no very enviable duty, and shall bring down upon our head the execrations of no inconsiderable number of men in our county. But we care not for this. We will not skulk to avoid a principle, though its advocacy should bring upon us the vengeance of the whole Republican host. The rights of the South for the sake of Liberty, is the motto we have taken, and which we will stand by or fall; for unless Southern rights, as secured by the Constitution, be acknowledged and enforced by federal legislation, this Union will be dissolved; its pieces baptized in blood, possibly to some other political faith, and liberty endangered if not totally destroyed. We shall go on in our feeble efforts in defense of Southern rights, and through evil nd good report bear testimony of fidelity to the institutions of our fatherland; and should fanaticism prevail, and the North pour upon us her excited hordes, may the “rocks and mountains fall on us” if we do not clutch the staff of the Southern flag.’

But the matter did not stop here; the Virginia Sentinel, true to its name, was watching the enemy, and in a lengthy article proved conclusively that ‘treason stalks abroad.’ The whole catalogue of Southern papers enlisted in the cause, and pledged themselves to exterminate this exotic Black Republicanism. They wished the names of ‘Mr. Ray’s confederates known, and hung up on every fingerboard and every tavern in the country.’ They proposed that the school in which I was teaching be turned into a ‘free soil hospital,’ for the benefit of those who were affected with the ‘malady of Republicanism.’ We who participated in that debate, were denounced as ‘violators of law,’ and ‘disturbers of the public peace.’

Language the most abusive and vituperative clothed the sentiments of honorable editors; and they called upon the good people of the Old Dominion to remove this blot from their otherwise fair history. One, in the height of his indignation, read to me the law which makes it a criminal act to deny the master the right 9legal0 of property in slaves, and another naively reminded me of those most potent Southern arguments – tar and feathers, and mob violence. Indignation meetings were called for the purpose of denouncing the acts of ‘that man Ray,’ who was evidently an agent of Seward, the prime-mover of Republicanism, which according to the brotherly editor, ‘was the devil incarnate on earth.’

Committees were appointed to wait upon me, and request me to leave the State, within a given time, upon pain of personal violence if I refused; and I yielded to the solicitations of friends. I am now in a free State – if not ‘the land of the brave,’ at least ‘the home of the free.’ That Northern people may know the degree of freedom enjoyed by the whites of the South, and the means resorted to to extinguish it, I submit the above, and conclude by asking them seriously the question – where freedom of speech and of the press is denied, where to talk upon the question of slavery extension, or the constitutionality of any law, is denounced as treason, is not a despotism already established? Are not even the whites enslaved? Such is our own country – our own American.

Is ours a land of liberty?

FRANCIS H. RAY Chatham, Col. Col, N.Y.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Reaction to the incident on March 15, 1856 was swift; several southern newspapers picked up the story, including the Virginia capitol newspaper, Richmond Enquirer of April 8, 1856:

And also the Richmond [VA] Dispatch Thursday, April 24th, 1856:

An African American newspaper, The National Era, printed in Washington, D.C., had a decidedly more supportive stance. The writer of this article seems to actually have been in attendance at the March 15, 1855 Goose Creek (not yet renamed ‘Lincoln’) Literary Society meeting. It is possible the author was Yardley Taylor or his brother, Thomas. A name jumps out of the article: James Trayhern. Mr. Trayhern is the author of the 1857 handbill posted around Loudoun County in criticism of Yardley Taylor and the Quaker community for their abolitionist/Underground Railroad activities. That handbill is found on this site on the page focusing on Yardley Taylor.

Here is The National Era April 24, 1856 article, followed by a transcription of the article:

For the National Era.

FREEDOM OF SPEECH IN VIRGINIA.

In the county of Loudoun, Virginia, there has existed, since 1851, a society, having for its object, as the preamble to its Constitution declares, “of free exchange of sentiment, the spreading of truth and mutual improvement”-and for its title, the ” GooseCreek Literary Society .” On the 15th of March last, a regular adjourned meeting of this Society was held at theGooseCreek School House, for the purpose of debating the question, “That we do endorse the nomination of Millard Fillmore by the American Party.”

At of previous meeting, the following parties were chosen to open the discussion, viz: Thomas Taylor and Henry Brown for the affirmative, and Francis H. Ray and Jesse H. Brown for the negative. In their replies, F. H. Ray and J. H. Brown argued that they could not endorse the nomination, upon the ground that the nominee was not opposed to the further extension of Slavery, that he signed the Fugitive Slave Law, &c. The former said, that with Washington, and Jefferson, and Franklin, and Jay, with the founders of our Government and the framers of our Constitution, he was opposed to the extension of Human Bondage over territory once concentrated forever to Freedom. The latter expressed similar sentiments; and concluded by adding that hope that deferral planes of Kansas and Nebraska might never, in the truthful language of the Senator from Alabama, (Mr. Clay,) “exhibit the painful signs of senility and decay apparent in Virginia and the Carolinas.”Neither of the Speaker’s argued upon the abolition of Slavery; but both said that they would not disturb the institution where it already exists, but would leave it to die out on the land that bred it.

After the chosen Speaker’s had concluded, and after several free speeches from others, James F. Trayhern was called upon for speech upon the affirmative. He responded in a lengthy and irrelevant speech, every graded that the discussion had turned into the Slavery question-although he spoke throughout from a half dozen pages of notes upon that question. He emphatically denied that Mr. Ray had the right of freedom of speech upon that question upon Virginia soil, although he himself devoted an hour and a half to its discussion. Hereupon, the meeting became much excited, and loud cries of “He has the right! he shall have the freedom of speech!” came from all parts of the room. At this point, Mr. Ray told him that if he or any other gentleman would come to New York, he would be allowed entire freedom of speech upon any and every question, and be treated with a respectful hearing. To which Trayhern responded, that “he (Ray) might have entire freedom of speech on Virginia soil, if he would speak right.” Mr. Trayhern then expressed the hope that Slavery might go into Kansas; that the South might never cease in its present efforts, until it should be firmly established there. He declared that, rather than see the Missouri Compromise restored, (strongly as he was opposed to its repeal,) he would see the Union dissolved. This sentiment gave rise to some hissing, and much excitement, and received a reply from Jesse Hoge. He said that he had heard long and loud denunciations of Northern fanaticism, but never of any that would compare with that, and that that was Southern fanaticism of the rankest kind. He was followed by H. Brown, Thomas Taylor, and others, (Americans,) all of whom declared that they could not endorse the kind of Americanism laid down by their would-be colleague, James F. Trayhern. Thus much for the facts relating to the meeting. Now for the sequel.

During the speech of James F. Trayhern, he was prompted repeatedly by Josiah B. Taylor-who sat at his elbow-editor of the Democratic Mirror, of Leesburg, Va., and organ of Henry A. Wise and his party. Soon after, the Mirror appeared within article under the title of “Black Republican Meeting in Loudoun.” Next followed the Sentinel and the Washingtonian, of Leesburg, and the Virginia Sentinel, of Alexandria, with articles denounce in those who conducted the negative of the above mentioned discussion as “Abolitionists,” “fanatics,” “violators of law,” “disturbers of public peace,” and other epithets expressive of their surprise and indignation.

The law which declares it to be criminal to deny the right of masters to property in slaves was printed, for the edification and enlightenment of Mr. Ray, with and he was advised, through the columns of the public press, to suppress his sentiments, and to beware of those potent arguments-tar and feathers, and personal violence.

Indignation meetings have been held in the different parts of the country, and resolution similar to the following, which we find in the county papers, and equally foreign to the subject, has been adopted:

“Resolved, That this manifestation of a reckless and disorganized spirit, the repeated violation of the policy of our laws, the thread disturbance of our peace, and such outrages upon our public honor, will, if persisted and, find an appropriate, if not effectual, remedy.”

Mr. Ray has removed to of free State, not because he feared the laws of Virginia, but because, consistently with the doomises held by the Society of which he is a member, he could not resist the threatening violence.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

More detail of Francis Ray’s quick departure from Virginia is found in the reminisence below, written by Anna Mae Sidwell, who had attended Springdale School. She wrote the following essay for Friends Intelligencer; it is transcribed by historian Bronwen Souders, Waterford, Virginia. The essay gets its title from Henry Russell, the young Quaker teacher who took over from Francis Ray after Ray left Springdale, but Sidwell covers the incident of March 15, 1856:

Henry S Russell at Springdale

Friends Intelligencer, Philadelphia, Pa., February 11, 1899 vol. 56 issue 6, p. 112

“In the interesting sketch of the life of Henry R. Russell in the Intelligencer of the 28th of First month, mention is made of his teaching at “Springdale boarding school for girls” near what is now Lincoln, Virginia; “founded by and under the management of Samuel M. Janney.”

There is a slight error in the statement which I, having been a pupil at that time, ask the privilege of correcting.

The “School for Girls” was founded by Samuel M. Janney in 1839, and conducted as such, by him, for a number of years; but in 1854, to meet the need felt by Friends of Fairfax Quarterly Meeting, and others, it was re-opened, under his management, as a school for both boys and girls, and continued under the new system, until its close a few years later.

As S. M. Janney was one of the earliest advocates of coeducation, and this, one of the first schools to adopt the plan, it is due his memory that his efforts in that direction should be acknowledged .

In reverting to those days, and the beginning of Henry R. Russell’s work in that school, some thrilling experiences come to mind, and all “Springdale scholars” who were there at that time, have vivid recollections of the “stirring events “which were but the premonitory “mutterings” of the storm which broke upon us in 1860 and 1861.

In the spring of 1856, when political feeling on the slavery question was intense, a few of the pro-slavery citizens in that vicinity used their endeavors to arouse prejudice against the school and its managers, especially Francis H. Ray, of Chatham, New York, who had been a teacher there since its opening the year before, charging him with expressing “incendiary” sentiments at a small debating society organized by some of the young man of the neighborhood for mutual improvement, and with no political aim whatever. The simple fact of his being from a northern state, afforded sufficient pretext for their prejudice and they persistently tried to “draw him out” on points “obnoxious” to their views.

[Para. Added] Although he stated his opinions in a moderate and dignified manner, trying to defend his position and ward off controversy, it was to no purpose. They misrepresented and condemned him, and strong and repeated threats of persecution being made against him, it was deemed best for his safety and the welfare of the school for him to leave the State. Arrangements were quietly made for a few of the older students, young men, to take him to the nearest station on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad some miles distant.

[Para. Added] It was a sad time when the word was cautiously passed around one evening that they were to leave that night. All the household were up to bid them “good speed, “and after tearful farewells they passed out into the darkness.

[Para. Added] The excitement was intense, but subdued, and figuring that they might be intercepted on their way, not until his faithful attendants returned, and reported F. H. R. safe on the other side of the Potomac, did we breathe freely again.

Having been a popular teacher, and sympathy for him increasing our interest, his departure under such painful circumstances left us “disheartened, “ if not “dismayed, “with the plans of the school unavoidably disarranged until a successor could be secured.

This successor was Henry R. Russell, whose task was not an enviable one, to take up the lines so sharply broken, and adjust them and himself to existing conditions but he quietly assumed the responsibility and faithfully performed his duty, served the remainder of that school term, and resumed the position of teacher there the following year. Waterford Va. signed A. M.S.” *

*Ann Marie Sidwell (5 Apr 1839-10 Oct 1907) daughter of Hugh Sidwell and Thamasin Haines of Hopewell Monthly Meeting, in Winchester, VA.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Francis Ray next turns up in a small notice in the New York Times on September 11, 1858 (shown below): “FRIENDS’ INSTITUTE – UNDER THE CARE of the Monthly Meeting of New York, situate [d] in the rear of Hester st. Meeting-house, will be re-opened on the 1st Second-day in Ninth Month. The school for Boys under the care of FRANCIS H. RAY. and that for Girls in charge of MILICENT B. MOREY, and the Primary Department by MARY BIRDSALL….”

Francis’ last newspaper notice came four years later, when the country was 20 months into a civil war. It was a brief obituary notice published in the New York Tribune on January 21, 1862 (shown below): “RAY – In this city, on Seventh day, 1st month, 18th day, of typhoid fever, Francis H., son of David and Lydia M. Ray, aged 26 years.”

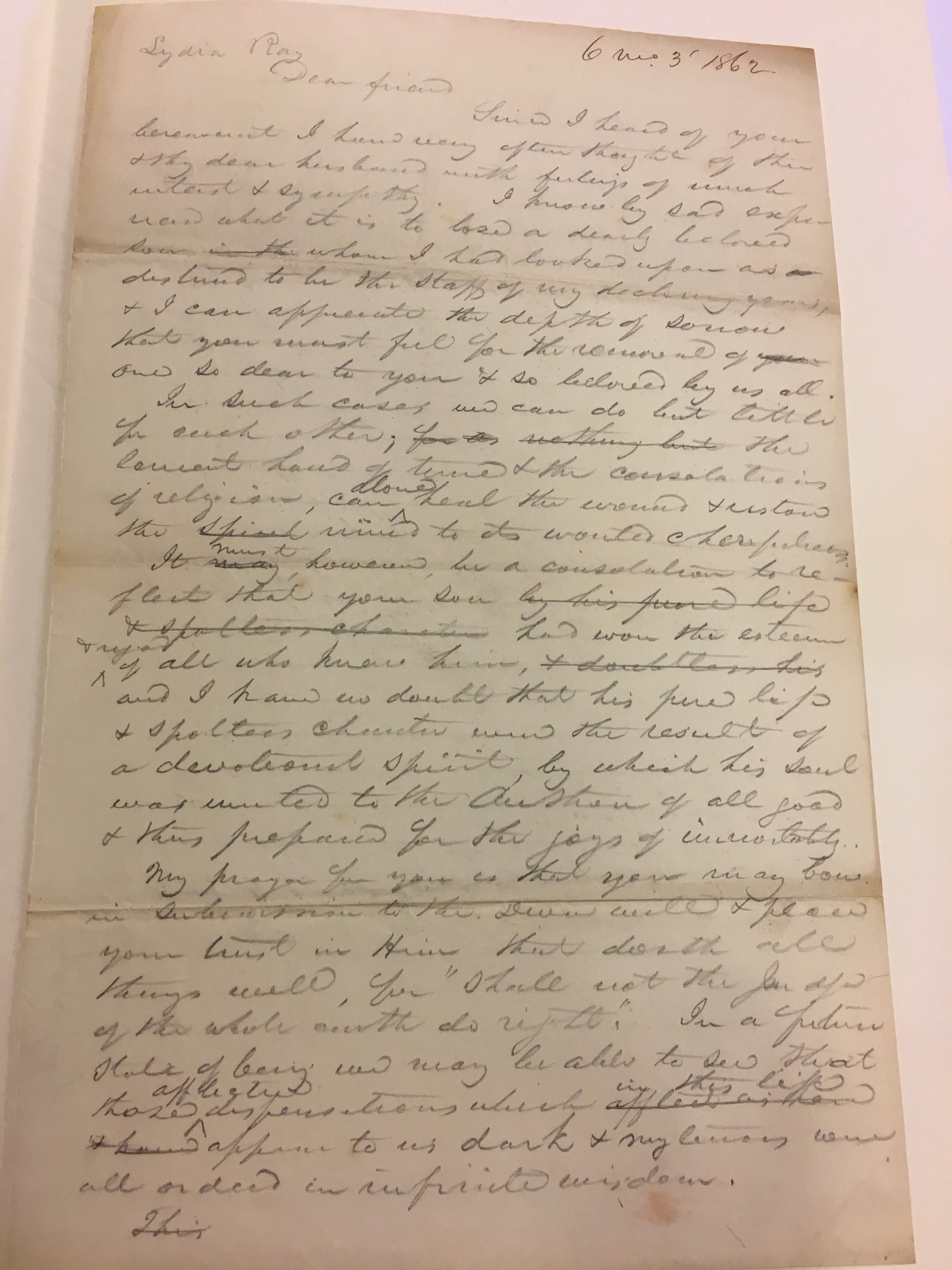

Francis was buried in Chatham Burial Ground, Old Chatham, New York, alongside his younger brother Albert who had died in 1860. Samuel M. Janney of Lincoln, Virginia had met Francis Ray when the young man taught at Springdale school in Lincoln, Va in 1855. Samuel Janney wrote a letter to Francis’ mother on June 3, 1862. This letter is a draft, and in found in the Janney papers in Swarthmore Friends Historical Library. It was typical of Janney to write drafts of letters sent. A typed transcription is below the draft of Janney’s handwritten letter:

6 mo 3’ 1862

Lydia Ray

Dear friend

Since I heard of your bereavement I have very often thought f thee & thy dear husband with feelings of much interest & sympathy. I know by sad experience what it is to lose a dearly beloved son whom I had looked upon as destined to be the staff of my declining years, & I an appreciate the depth of sorrow that you must feel for the removal of one so dear to you & so beloved by us all.

In such cases we can do but little for each other; the lenient hand of time & the consolations of religion can alone heal the wound & restore the mind to its wanted cheerfulness.

It must, however, be a consolation to reflect that your son had won the esteem & regard of all who knew him, and I have no doubt that his pure life & spotless character were the result of a devotional spirit, by which his soul was united to the – of all good & thus prepared for the joys of i-.

My prayer for you is that you may bow in submission to the Divine will & place your trust in Him that doeth all things well. You “shall not the Judge of the whole earth do right.” In a future state of being we may be able to see those dispensations which in this affliction appear to us dark & mysterious were all ordered in infinite wisdom.