Harry was in a terrible situation: it was 1828 and Harry was an enslaved man in northern Virginia. Because Harry was enslaved, he had no documented surname. On learning that his owner, a “Miss Allison” of Stafford County, Virginia, was planning to sell him to slave traders to take him further south, Harry decided to escape.

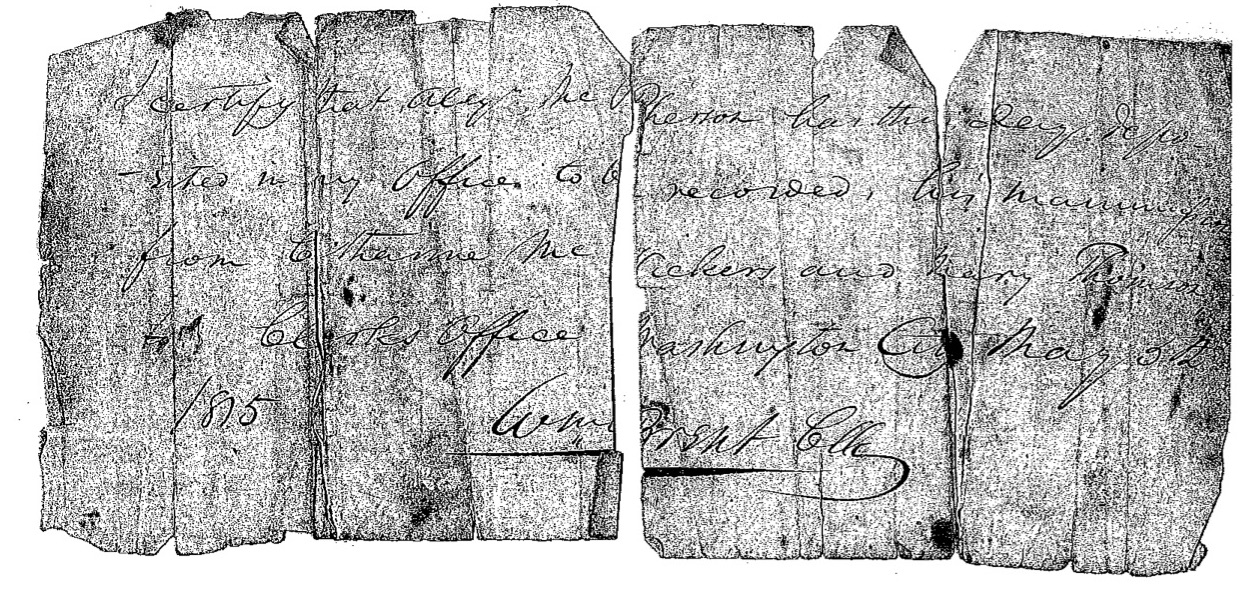

Harry’s labor was being rented out by his owner to a man named Samuel Cox, in Loudoun County. Loudoun County was closer to the free state of Pennslyvania than where Harry normally lived and worked. He decided to take a chance and approach a free black man named Alex McPherson, asking to borrow McPherson’s manumission “freedom paper.” This paper was a court document that must be carried by all free blacks verifying their freed status. Alex McPherson, at great risk to his own safety and liberty, agreed to lend Harry his paper, but insisted the paper be returned to him as soon as possible. Harry would carry the paper north. If the worst happened and he was stopped and questioned along the way, Harry planned to show the paper and claim to be a free man.

Before leaving northern Virginia, Harry needed to learn the best route north. Once safely in a free state, he would need a job and place to live. For this help, Harry turned to local Quakers. It was common knowledge where the Loudoun County Quaker communities were located, including the village of Goose Creek (later re-named Lincoln.)

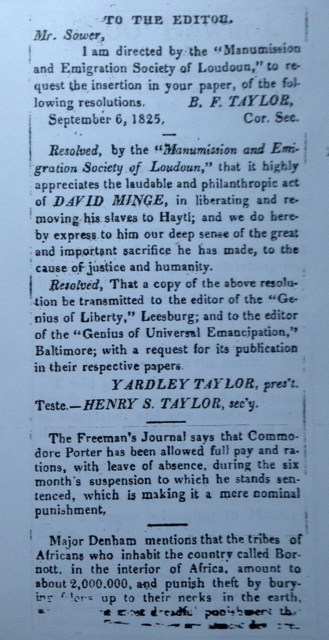

Harry would end up at the home of Yardley and Hannah Taylor. Yardley Taylor was a farmer and a mail carrier for Loudoun County. The Taylor’s ran a tree nursery at their property, ‘Evergreen,’ on the edge of Lincoln. From the 1820’s through 1850’s Yardley gave public speeches against slavery and wrote abolitionist articles and letters to Leesburg newspapers. He was president of various anti-slavery societies. Here is a newspaper article describing an “Anti-Slavery Convention” Yardley Taylor and other Virginia abolitionists attended. The convention was held at the one room school house near Goose Creek Meetinghouse, in Lincoln:

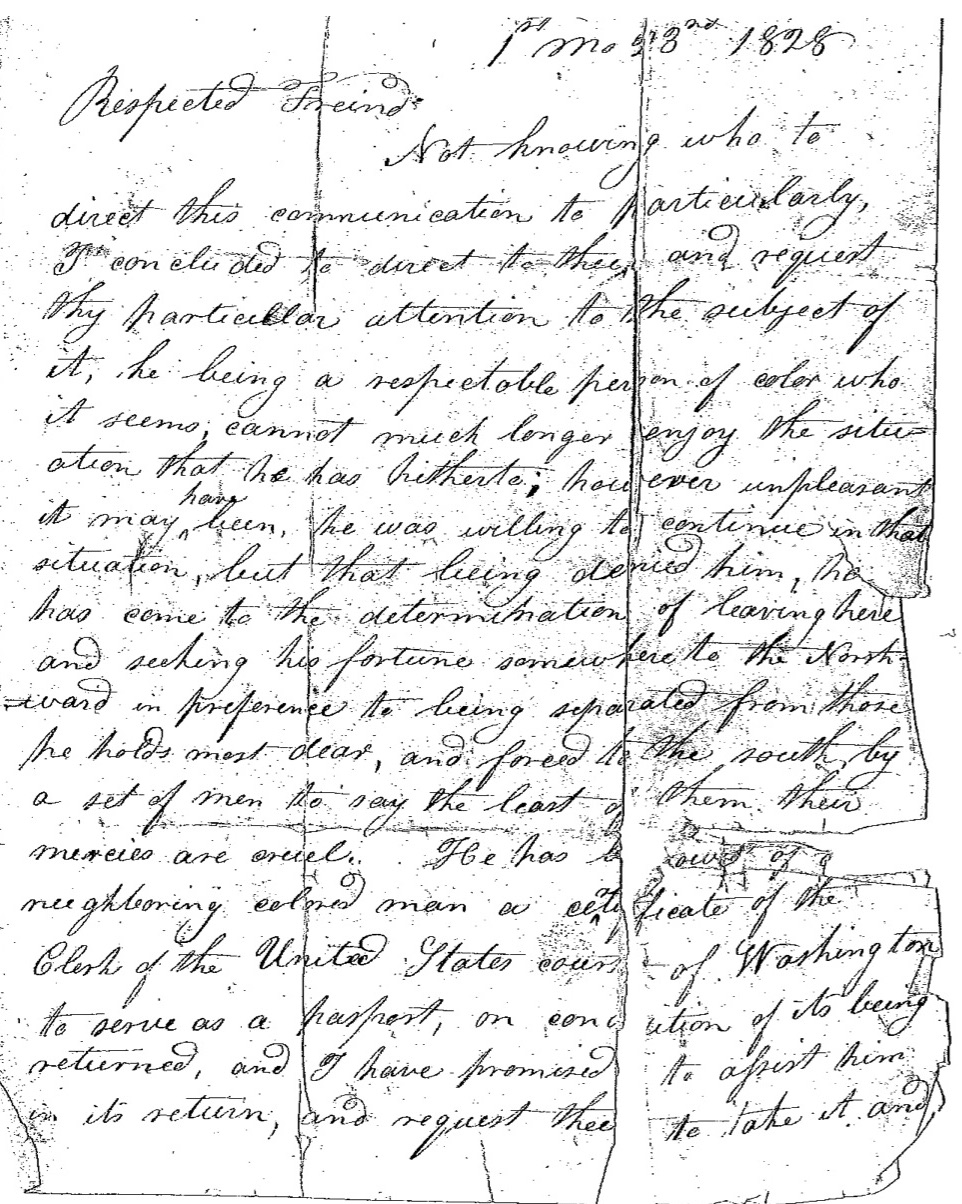

Did freedom seeking, enslaved Harry know of Yardley’s abolitionist efforts? On Jan. 23, 1828, Harry approached the home of Yardley and Hannah Taylor, near Lincoln, and asked for help. Yardley agreed to help him, writing a letter for Harry to carry north to fellow Quaker Jonathan Jessop of York, PA, a man experienced in helping slaves escape bondage. The term ‘Underground Railroad’ didn’t become common until the 1840s; Harry, Yardley Taylor and Jonathan Jessup were acting in a way that would eventually define that term.

Yardley’s letter (see below) to Jessop explained that Harry was “a man of good character,” who was to be sold to slave traders. Yardley wrote Harry would be “forced to the south by a set of men who to say the least of them their mercies are cruel.” Yardley asked Jessop to return Alex McPherson’s freedom paper quickly. He warned that the paper must not be mailed back, but sent in person by “safe conveyance.” Yardley Taylor possibly thought his own mail was under surveillance.

Trascription of Yardley Taylor January 23, 1828 letter carried by fugitive enslaved man Harry to Jonathan Jessup, York Pennsylvania:

1st mo [January] 23rd 1828

Respected Freind [sic]

Not knowing who to direct this communication to particularly, Ive concluded to direct to thee, and request Thy particular attention to thesubject of it, he being a respectable person of color who it seems, cannot much longer enjoy the situation that he has hitherto; however unpleasant it may have been, he was willing to continue in that situation, but that being denied him, he has come to the determination of leaving here and seeking his fortune somewhere to the Northward in preference to being separated from those he holds most dear, and forced to the south by a set of men to say the least of them their mercies are cruel. He has borrowed of a neighboring colored man a certificate of the Clerk of the United States court of Washington to serve as a passport, on condition of its being returned, and I have promised to assist him in its return, and request thee to take it and forward it to me by a safe private conveyance, that it may be returnd to the propert owner.

My conduct in this respect would be censured pretty strongly by many here, and if proven might subject me to some difficulty, and indeed it is not pleasant, but when a fellow creature groaning under servitude, with the prospect of its being rendered doubly severe, and requests a favor of this kind I cannot deny him. If no private conveyance should offer pretty soon please drop me a few lines by post directed to Purcells store post office to let me know how he has got along-but be particular about the certificagte and send it byt safe conveyance and oblige thine [friend]

Yardley Taylor

Loudon [sic] County

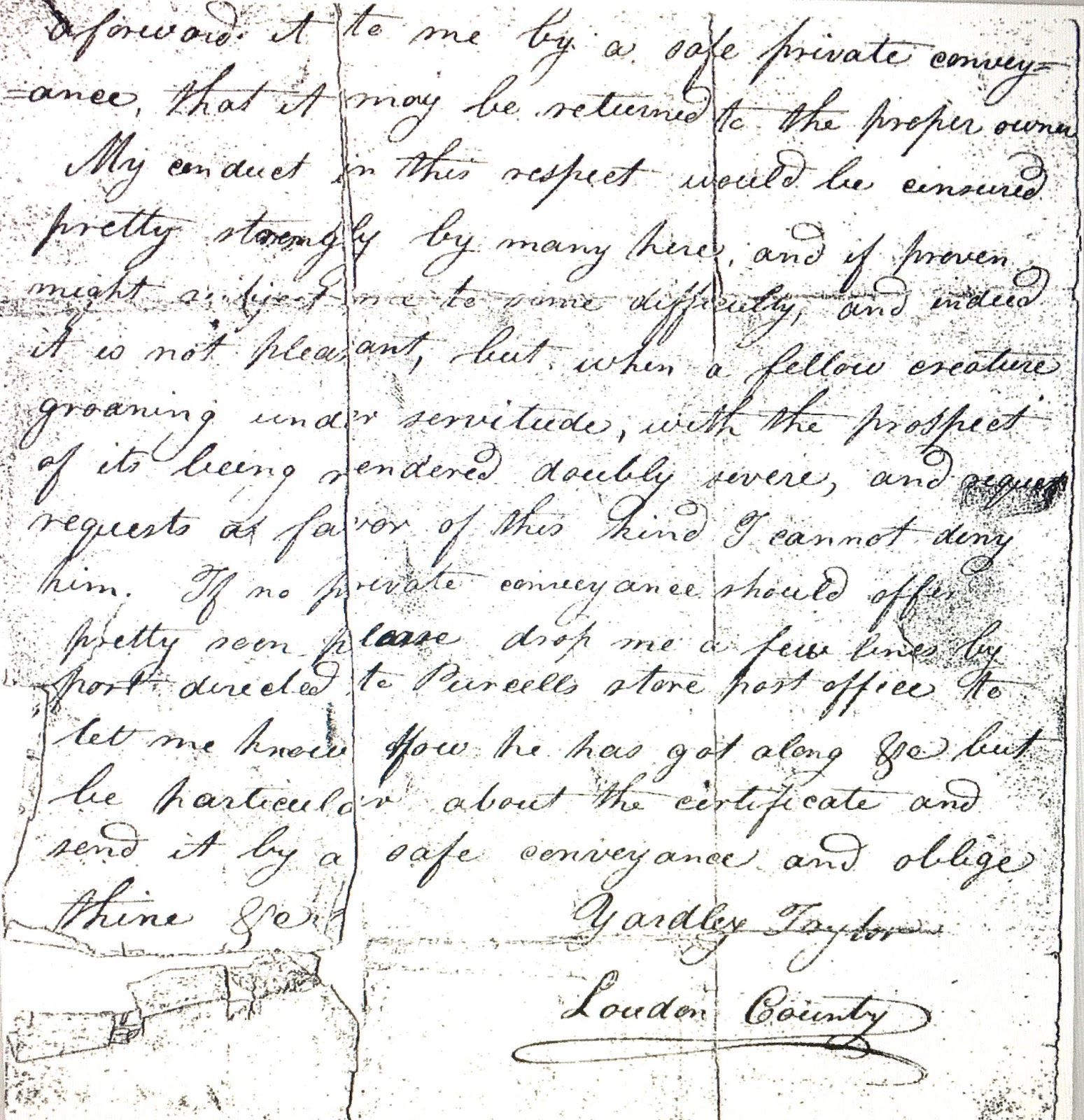

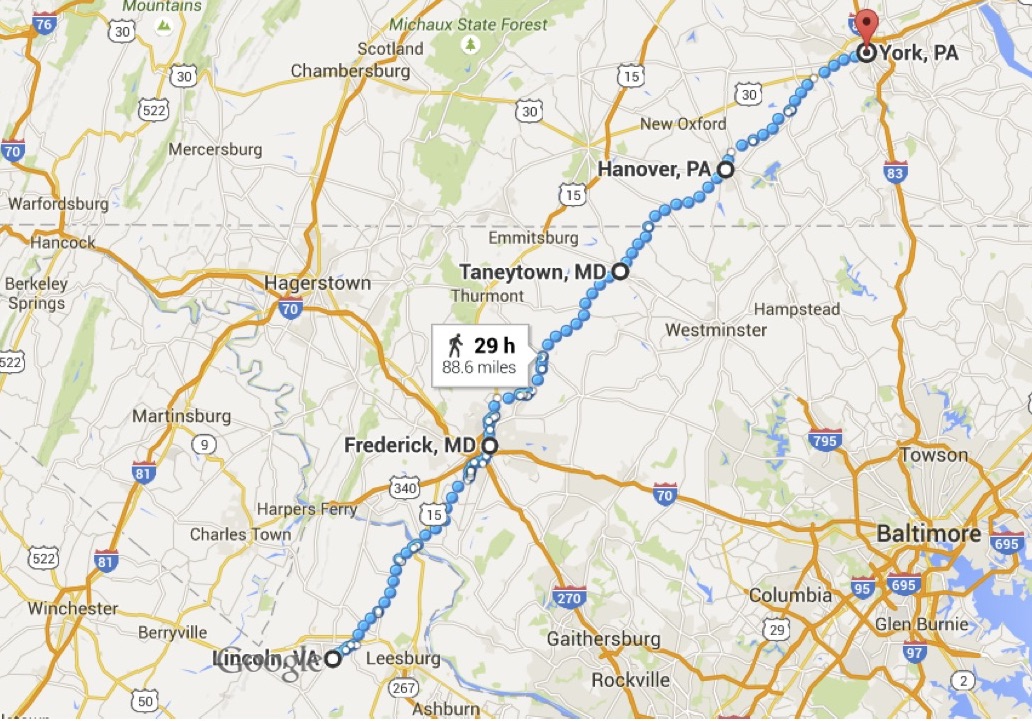

Yardley also gave Harry a small piece of paper which listed six towns through which Harry would pass on his journey to York: “From Frederick to Woodborough 13 miles Taneytown 14 miles… .” This information would direct Harry as he walked from town to town on unfamiliar roads.

A modern mapping of this route shows how precise and straight it led north to safety. Had Yardley Taylor or someone he knew, mapped this route out previously? Had it been used before?

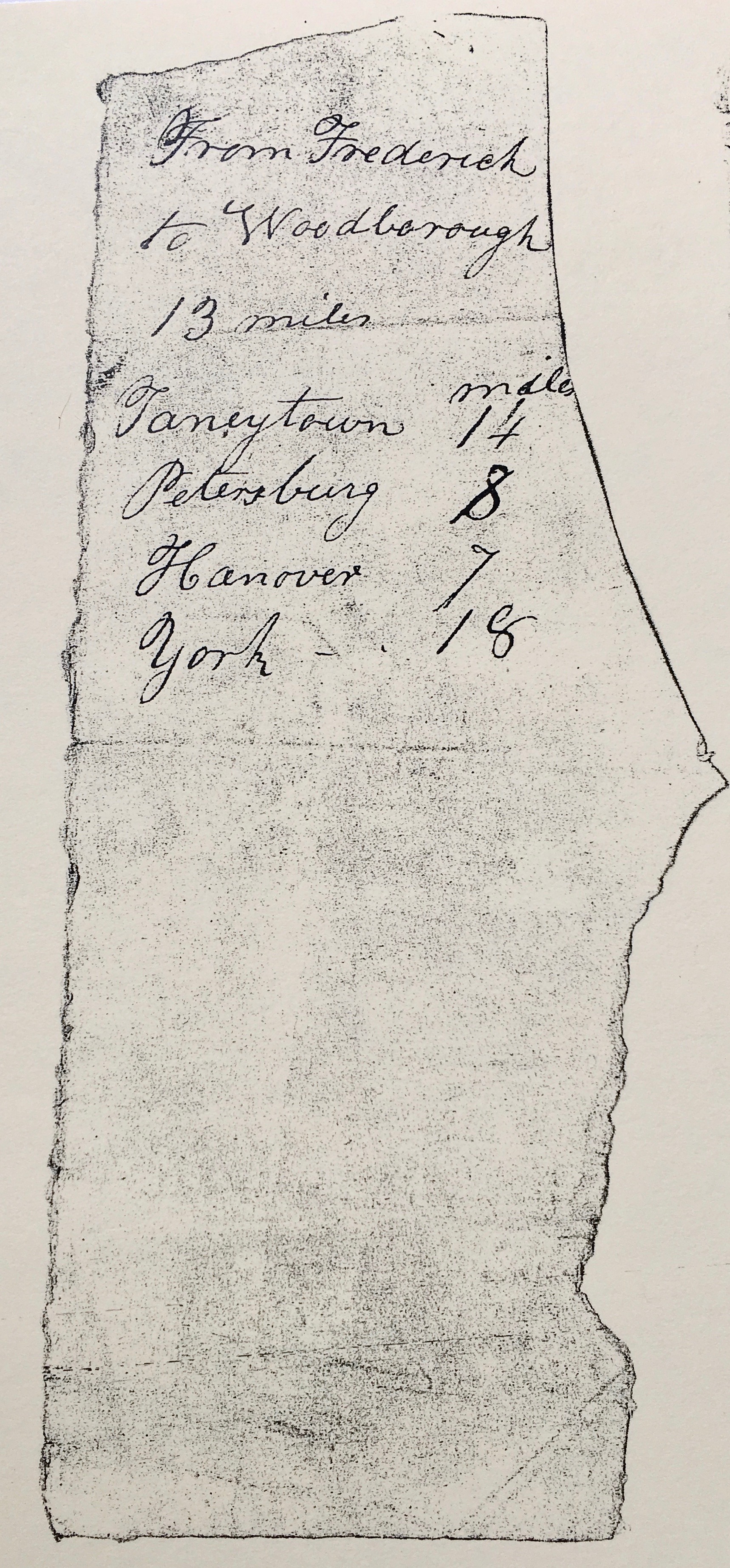

The envelope Yardley addressed to Jessop, containing Yardley’s letter, also bears different handwriting:

“This Taken by me from Negro slave named Harry the 28th day 1828 January, belonging or as he says to Pa [Pennsylvania] … Jonas Dixon.”

Dixon’s notation on the envelope explains a tragedy: Harry got caught. Five days after receiving Yardley’s help on Jan. 23, Harry was stopped and questioned by Dixon, who possibly was a slave catcher on Maryland roads. (More research on Jonas Dixon is needed.) When stopped, Harry would have shown the freedom paper and claimed that he was Alex McPherson. That ruse obviously didn’t work. Once Harry’s pockets were searched and Yardley Taylor’s letter was found and read, the desperate gamble was lost.

Harry was brought back to Loudoun County and put in the Leesburg jail. Virginia law punished an attempted slavery escape with public lashing; the Leesburg courthouse grounds had a public whipping post for such occasions. Public punishment set an example and served as warning to other slaves. Harry’s owner would have been contacted to come to Leesburg and pick up her property. Either she or her farm overseer would come and take Harry back to Stafford County, maybe to physically punish him further. Then what Harry most feared – being sold to slave traders and forced south – would have happened. After all, that is what his owner had intended for him before his escape. Now she had all the more reason to sell Harry: he had proven himself to be troublesome.

By loaning out his freedom papers, Alex McPherson might find his own freedom in jeopardy; Virginia law forebade helping a slave escape and punishment for freed blacks helping in this manner was to lose their own freed status. (Again, further research is needed to find McPherson’s fate.) McPherson would not be able to assert that his papers had been lost or stolen because Yardley Taylor’s letter laid out McPherson’s involvement. Knowing Alex was vulnerable to harsh punishment would have added to the misery felt by both Harry and Yardley when the escape effort failed.

Yardley Taylor was arrested for “enticing, persuading and advising a certain negro slave named Harry… .” Yardley was put in jail in Leesburg. Neighbor and fellow Quaker Daniel Cockrill posted Yardley Taylor’s $500 bail. Yardley pled Not Guilty and the case dragged on for two years. Finally, Yardley changed his plea to Guilty, and paid a $20 fine plus costs.

The documents: Alex McPherson’s freedom paper, Yardley Taylor’s letter to Jonathan Jessup of York, Pennsylvania, Yardley’s paper listing towns/mileage, and the letter envelope, as well as several warrants from the Loudoun County sheriff regarding Yardley Taylor court appearances for “enticing persuading & advising a certain negro slave named Harry the property of Miss Allison of Stafford County from the employment & possession of Samuel Cox of Loudoun County …” are all in the Loudoun County Courthouse Historic Records and Deeds Research Division, Leesburg, VA. They are public records; anyone can request to see the documents. They are rare pieces of our American story.

Yardley Taylor was President of the Loudoun County Manumission and Emigration Society during the middle of the 1820’s, and perhaps kept that position leading up to his arrest in 1828. The nation’s Manumission and Emigration Society chapters were dedicated to buying the freedom of enslaved men and women, then paying for their passage to Liberia, in western Africa. When that long ocean voyage proved too financially prohibitive, the Societies began raising money to send freed slaves to the newly established country of Haiti.

Eventually many anti-slavery activists found the notion of raising money to send formerly enslaved men and women abroad to be both impractical and wrong: why should black Americans have to leave the country to live free? The focus remained on manumission and outright abolitionism.

A column written by Yardley Taylor in his role as President of the Manumission and Emigration Society can be found here. The column makes clear the Society also worked to education and persuade Americans that slavery was against their own self-interest, as well as being an immoral institution unworthy of such a great nation.

After Yardley Taylor’s 1828 arrest, he eventually reclaimed his life’s routines: grafting apple trees, delivering mail, attending Goose Creek Meeting regularly, with his extended Quaker family. He never gave up abolitionist efforts, however, and regularly wrote letters to the local papers on the topic. In 1856 new attention was drawn to Yardley and his fellow anti-slavery activists of Lincoln, when national newspapers picked up on a meeting held at their village school. That extraordinary episode has a page on Nest of Abolitionists, found here. One result of the incident was this broadsheet, posted around Loudoun County:

TO YARDLEY TAYLOR, ESQ.

SIR: There are but few persons in the county, I presume, who have not heard of you as the Chief of the abolition clan in Loudoun. I am free to award to you this position, for the bold –which you have uniformly exhibited in promulgating the odious doctrines of your sect, fully entitle you, in my opinion, to the distinction.

Although your name has gone abroad and you are pretty generally known, through the county at least, yet there are some persons, I have no doubt, who have never had the pleasure of seeing you. For their benefit, as well as for your own, (for you certainly have never seen yourself as others see you,) I propose to describe as well as I can, your personal appearance. My method of executing this task may appear to many as somewhat novel, but as it was the first plan that suggested itself to my mind, I have adopted it.

To see you to advantage, the spectator should station himself in the middle of the turnpike at Heaton’s Cross-roads, on the bright summer afternoon on an eastern mail day, at about “two or three o’clock.” If he will now look straight down the road leading to Goose Creek, ten to one he will soon see emerging from the wood at the end of the lane, a square built, heavy set, hugely footed, not very courtly figure of an old man, mounted on the vertebre of a somewhat lusty animal, with one hand tightly grasping the rein, and the other holding on, – like the witch to the tail of Tam O’Shanter’s grey mare, Meg, – to a little black bag (Pandora’s box was nothing, I imagine, but a little black bag after all) containing the Goose Creek mail.

Such is the remarkable personage as he appears to the spectator from the stand-point above indicated, riding along in a brisk trot, with a demure visage and meditative air; tormenting his brain, it may be, to discover a more successful method than has hitherto been pursued of relieving his neighbors of the encumbrance of their slaves, or else (and this is the more charitable supposition) taxing his genius to devise some plan for resisting the depredations of the Krout weed.

I am well aware that the picture I have drawn is far from perfect. To do full justice to your figure would require the pencil of a Hogarth. Imperfect as the portrait may be, I have no doubt it will enable you to recognize the original.

Having endeavored to describe your person, I now propose to portray your character. This I shall do by an examination of your principles and conduct.

Let me begin by an inquiry into your motives for seeking an interview with me at this late day. More than a year has elapsed since your abolition demonstration at Goose Creek, and the excitement which it produced has long since subsided. Did you mistake the calm which followed for a verdict of acquittal, and suppose that sympathy had taken the place of resentment? – This must have been your reasoning, or surely you never would have hazarded the expression of such revolting sentiments, or made such a confession of guilt in public as you did in the conversation which took place at the interview referred to. It may be you had the folly to imagine that you might obtain from me a recantation of something I had previously said. If this were one of your motives, you were never more mistaken. I have nothing to recant, as I then distinctly told you. And you are laboring under an equally gross delusion, in my opinion, in supposing that the time has come when you can preach your incendiary doctrines with impunity. Or did you seek this talk with the view of ascertaining how far you dare go in your assaults upon Southern institutions? But I shall prosecute the inquiry no further.

You commenced the conversation by declaring your entire innocence of the charge upon which you were arrested and brought to trial of aiding in the escape of a fugitive slave; but when subjected to the test of a searching examination you admitted that a runaway slave came to your house; [it seems rather singular that all the runaways should stumble upon your residence, but of course it is all accidental,] that you knew him to be a runaway slave; that you took him by the hand and led him gently in, and fed him, and after furnishing him with a letter to a friend in Pennsylvania, sent him on his way rejoicing. And what was your apology for this atrocious offence? – that you were acting in conformity with the principles of your religion. Monstrous! Monstrous! This was the excuse offered by Mahomet to palliate the guilt of his wholesale destruction of human life. It was the plea of the infamous Charles of France and his Catholic minions for putting to death in one single night seven thousand of his Protestant subjects. And in later days the abominations of Mormonism, and the A—are justified upon the same ground. Oh Yardley! Yardley! Who would have dreamed that your own confession could make your guilt so clear.

The opinions you avowed on that occasion were equally startling with the confession you made. You very gravely maintained that when the municipal law fails to square with your own peculiar notions of that “higher law,” of which you are the advocate, your obligations to the government extend no farther than a submission to the penalty. – Have you ever reflected upon the consequences of this dangerous doctrine? It justifies resistance to all positive law. The act of Congress providing for the reclamation of fugitive slaves may be resisted, trampled upon even to the forcible taking of the slave from the lawful custody of the officer or owner, and to the taking of life itself, without the fear of violating a single moral obligation, if this doctrine be earnest. Where death is the penalty, how disastrous soever the violation of the law may have been in its consequences, all that the offender has got to do, is to surrender his body to the executioner, and his soul, released from its bonds, goes straightly to Heaven.

The principle of moral and positive laws is the same, and the same obligation rests upon us to obey the one as the other. The good man makes no distinction. The object of penalties is to enforce obedience to the laws, by deterring men from their violation. They are not designed as a equivalent for the commission of an offence. A man is, therefore, very far from performing his whole duty to society by simply submitting to the penalty of a violated law. He is under a high moral obligation to do more than this – he must obey that law. The Bible, morality, and patriotism, all alike unite in enjoining it as a solemn duty which every man owes to the government which affords him protection.

Knowing you as well as I did, I was prepared for the announcement of sentiments the most revolting in their character, provided you were candid and bold enough to give them utterance; but really I was perfectly astonished when you suggested the difficulty of adducing any more valid objections against marrying a negro wench, than in wedding an Indian beauty. Comment here is unnecessary.

You told us something about the trouble some of your neighbors and confederates in crime got into, in a neighboring County of the State. I remember hearing an account of this long ago; but the version then given, was very different from the one you gave. There are a few prominent facts connected with the affair, of which I have the most distinct recollection. These gallant Knights of the Black-faces were down South it seems, on some sort of a negro expedition. Pretty soon after arriving on the field of operations, the object of their — leaked out by some means, and thus found it necessary for their comfort and safety to beat a precipitate retreat, in order to avoid the consequences of the indignation they had excited.

I remember, also, hearing many years ago the story of Lovett’s Phil. You were personally concerned in this affair, I believe. I am sorry it did not occur to me to mention this subject to you, on the occasion of our talk the other day; as I have no doubt you would have given the particulars with all the frankness with which you narrated other of your adventures. I think, however, you succeeded in putting Phil through. The success which has invariably attended your efforts in this line, would seem to argue the possession of no small degree of skill in the business: a fact which is well known, I dare say, and properly appreciated in a certain quarter. This accounts, I presume, for the immensity of your abolition correspondence of which you spoke. You told us, however, that your Northern allies complained of you. Perhaps you are not accomplishing quite as much as they have a right to expect from the superior skill and ability with which you have heretofore managed the affairs of the Under-Ground Railroad Company. You might plead to these complainings by showing that your location, although as favorable, or perhaps, more so, than any other in the South, yet from the very fact of being in a quasi Southern county is not quite so propitious a point for the prosecution of your philanthropic labors, as if the entirety of its surrounds were anti-slavery. I am well aware, however, that to all this it could be replied, that the immediate vicinity of your residence is entirely favorable to the furtherance of your designs; while beyond the limits of this neighborhood, and through the County generally, your principles have made such inroads, and are acquiring such an influence, that the difficulties which have hitherto opposed you, are becoming less formidable every day, as well as rapidly diminishing in number. You said much more in that talk; but I will let it pass for the present.

There are some points upon which I desire more information than I possess; will you have the kindness to enlighten me? Is Loudoun indebted to you for the distinguished honor of having one of her citizens – a near neighbor of yours – appointed Trustee of the African Female Seminary in the national metropolis? Who was the wretch that wrote that slanderous, blackguard, scurrilous, dirty, vile, miserable doggerel letter, which was read all over your neighborhood, and then sent me through the mail? Is it a fact this obscure production was publicly read in one of your Goose Creek Schools, for the benefit of the pupils? This letter was only one of the many wrongs, you and your adherents, have done me. Think you I can easily forget such treatment? It was with the view of screening yourselves from the consequences of the grievous wrongs you had committed at the Goose Creek meeting, that you wantonly assailed me with that tissue of falsehoods which appeared in the Alexandria Sentinel. “He is poor –unsustained by family influence, or wealthy connexions, and it will be an easy matter to shift the burden of our sins on to his shoulders; for we are powerful: – it will crush him and save us.” This was your reasoning. But you have neither crushed me, nor have you deterred me from exposing your vile conduct.

A few more words and I have said enough –people of — are not yet sufficiently imbued with your principles to tolerate any flagrant interference with their slave property; yet, judging from my observations of the last few years, I believe the time must soon come – if you will only exercise the proper discretion – when you need fear nothing. Many slave-holders already feel and fear your influence, and hold their tongues – I allude to the influence of your party. It deters the public functionaries of the County from the performance of their duties and entails upon the community evils which our laws are powerless to remedy. But this influence does not stop here, ——- Your obedient servant, J. [James F.] Trayhern July 28, 1857

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Further Reading: Yardley Taylor and Samuel M. Janney are mentioned in a anguished Reconstruction letter.

Yardley Taylor’s nephew Kirkbride Taylor chose to fight for the Confederacy when war broke out in 1861. Here is Kirkbride Taylor’s story.

Hannah Brown Taylor (1795-1880) was Yardley Taylor’s wife and the mother of eight children. She worked alongside her husband at Evergreen Farm. Her daguerreotype can be seen here.