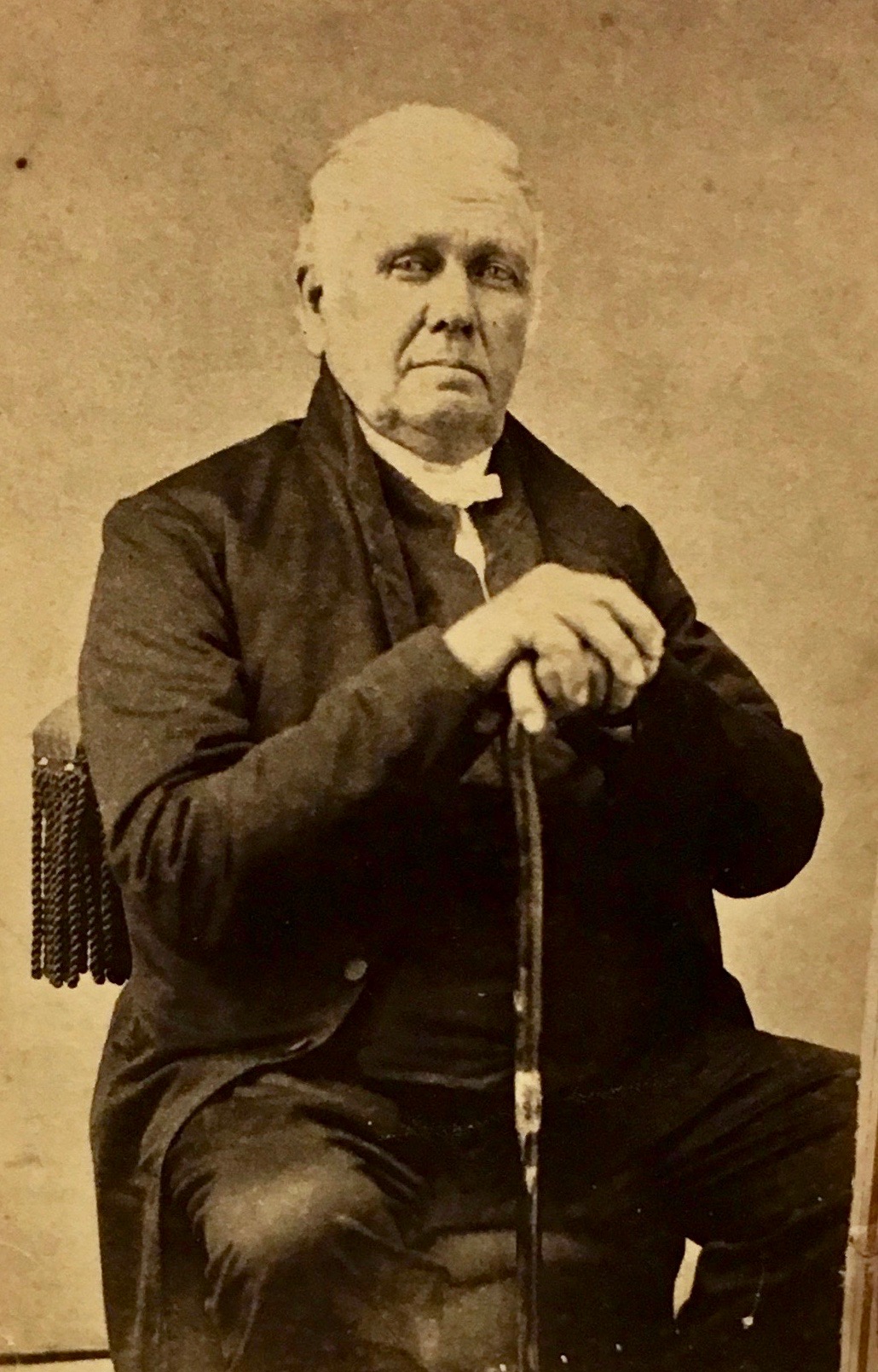

William Tate (1796-1884) was an outspoken abolitionist and, according to family members, was active on the Underground Railroad in northern Virginia. William and Priscilla Tate are discussed in the Kitty Payne/”…case in Rappahannock” page of this website. Tate descendants claim that possibly two of William Tate’s sisters were also active Underground Railroad participants.

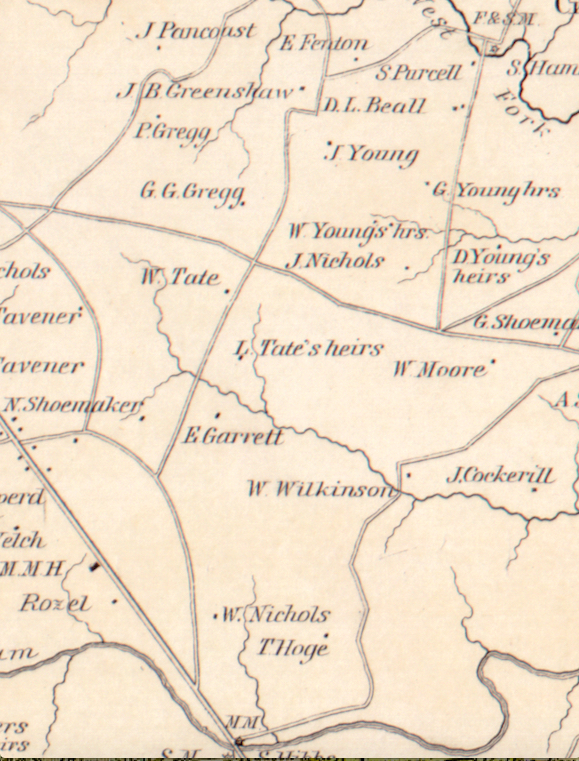

The “W. [William] Tate” property location was a short distance outside Lincoln, shown by Yardley Taylor for his 1853 Loudoun County map. The extended Tate family owned property on both sides of Greggsville Road, with William’s father, Levi, denoted on Yardley Taylor’s map by the words “L Tate’s heirs.”

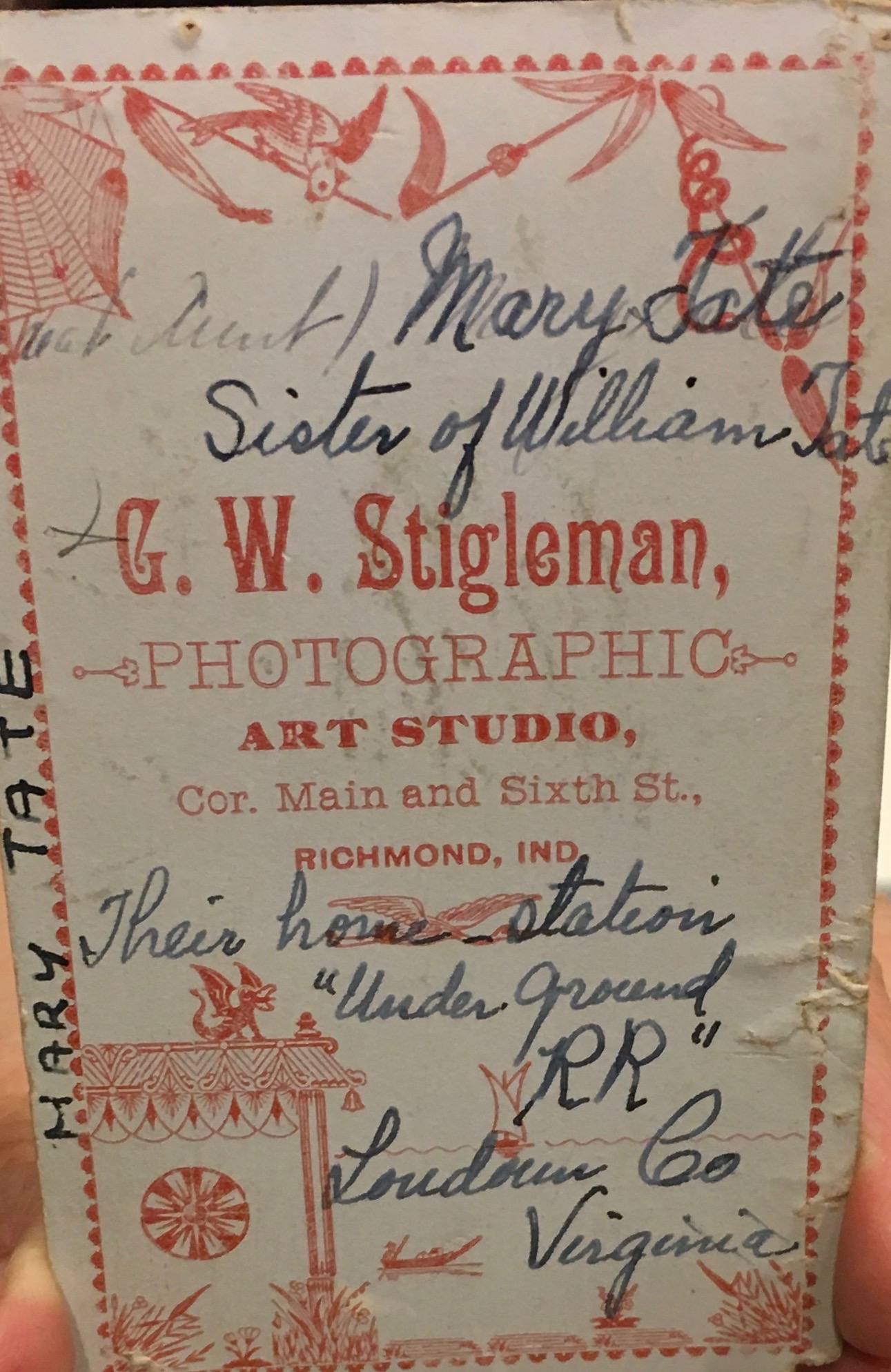

Two of William Tate’s sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, lived in the “L Tate’s heirs” house, originally home to their father Levi Tate and mother Edith Nichols Tate. It was the home in which the sisters and William, along with four other siblings, grew up.

The W. Tate and L. Tate property is shown near the crossroads of Greggsville Road and North Fork Road, outside Lincoln and near the village of Philomont.

(A full view of the Yardley Taylor map may be seen at a link here.)

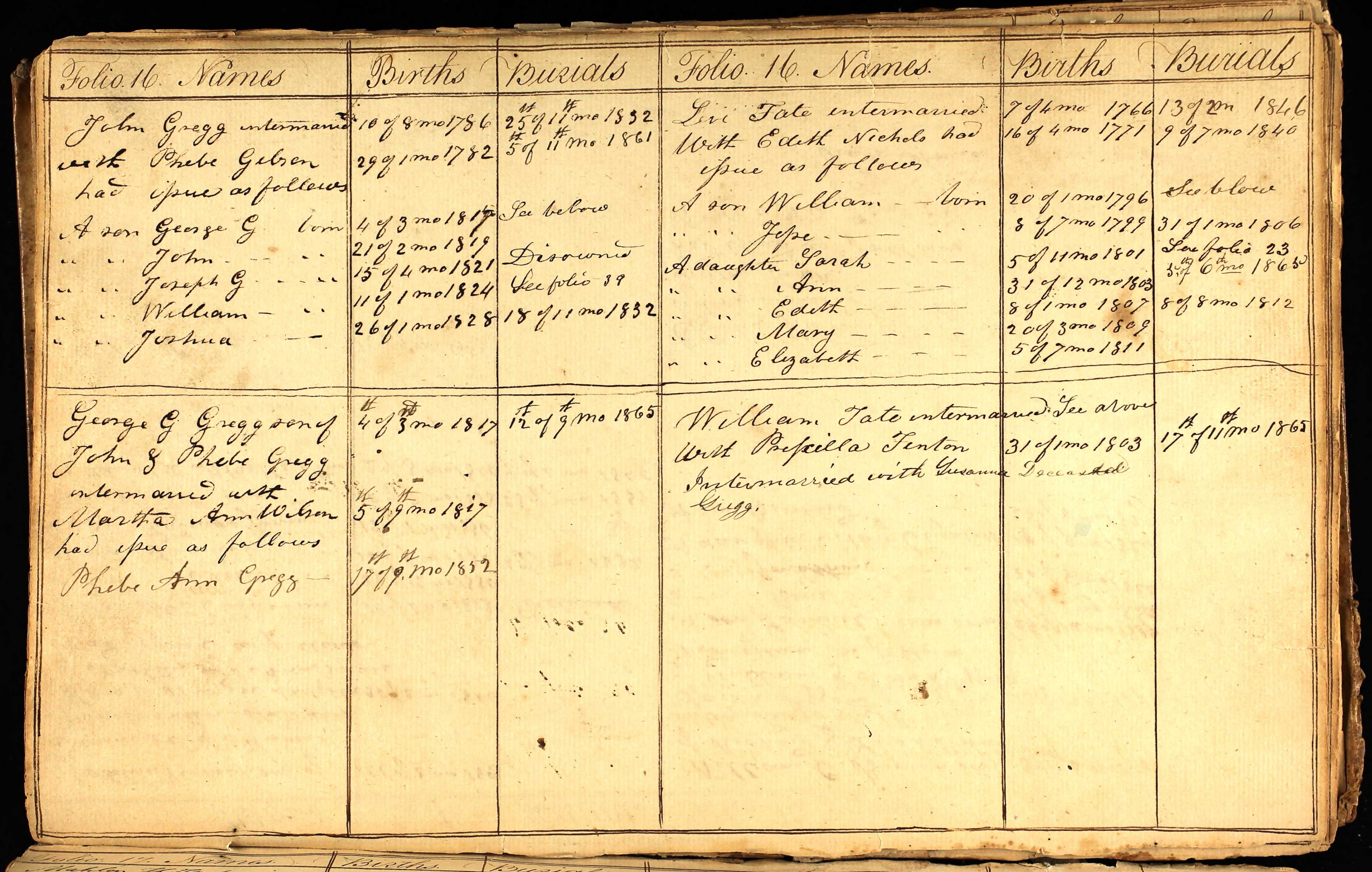

William Tate and his wife Priscilla had no children. Priscilla died in 1865, and William married again; his second wife was fellow Goose Creek Meeting Friend and neighbor Susanna Gregg according to Goose Creek Meeting minutes, as seen below:

William Tate was a force to be reckoned with; he lived his entire, long life in the farming neighborhood of Goose Creek Meeting. He was central to Meeting business, his name turning up repeatedly in the Society of Friends’ official minutes, whether traveling to Baltimore Yearly Meeting on religious matters or taking part in local Meeting management.

In August, 1845, Tate was involved in a frightening and violent episode associated when he and some fellow Quakers’ aided a black woman, Kitty Payne, and her children. Kitty Payne had been freed by her mistress, and she moved with her young family to Pennsylvania. But she and her children were kidnapped in Pennsylvania and brought back to Virginia to be returned to slavery. That event is discussed here, with primary source material. Remarkably, even after this dangerous event, William Tate continued to be active in anti-slavery efforts…fearless.

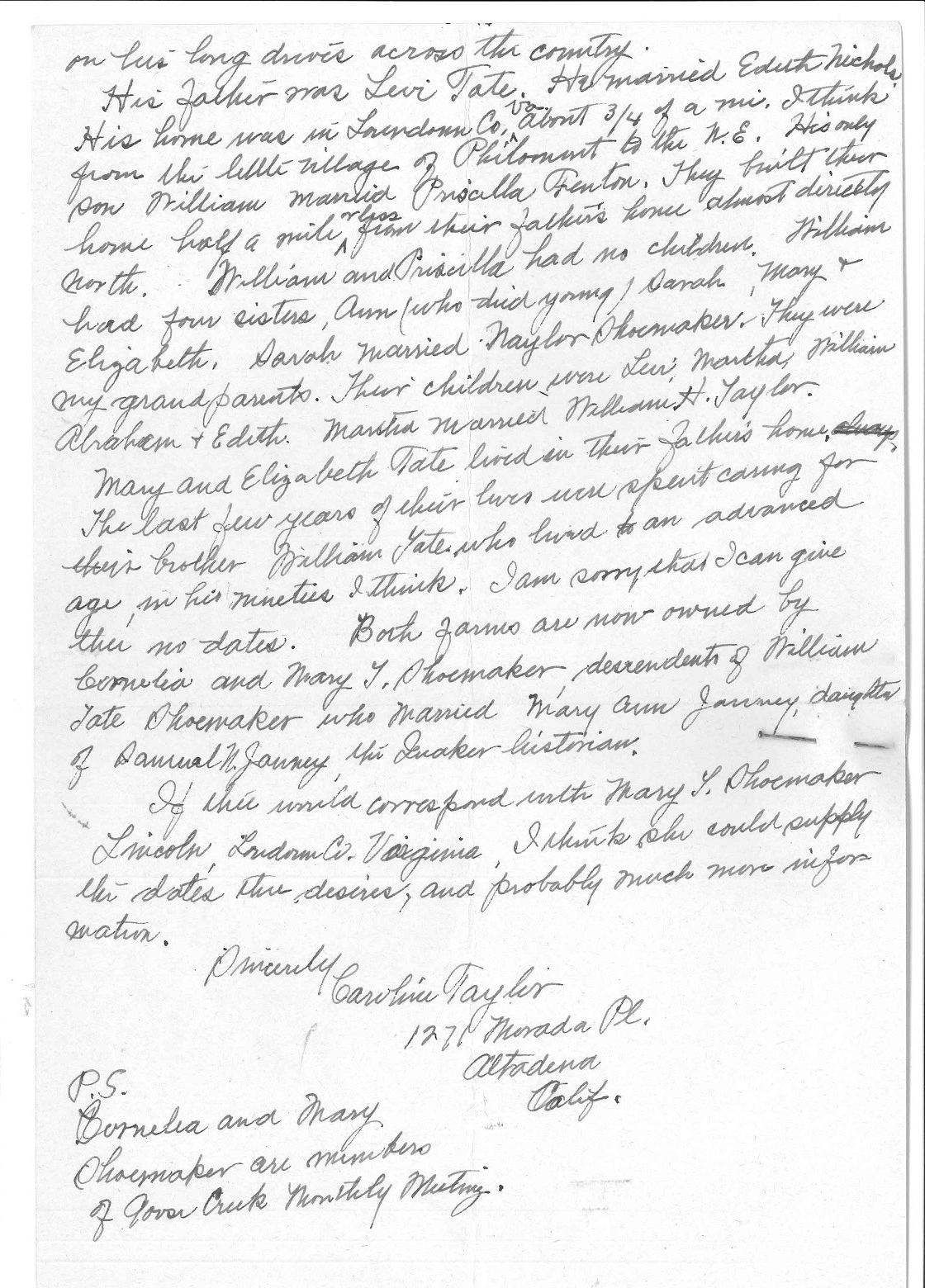

When she was an old woman, William Tate’s neice, Carolyn Taylor, wrote a letter to Quaker historian Albert Cook Myers, in which she gives a brief but insightful description of her Uncle William (transcript below scanned letter):

“1271 Morada Pl. Altadena Calif.

Mar. 6-1945

To Albert Cook Myers

Moyland [sic] Pa.

Dear friend,

I think Mariana Rawson made a mistake in giving thee my name, for genealogical data. I am so far removed from my old Va. home. I have not carried the family records with me.

I was born in my great Uncle William Tate’s home, and lived there the first four years of my life. My father, William H. Taylor was at that time caring for the farm of my great uncle.

I have a child’s memory of Uncle William, a large white haired man, and I have been told of his work in the anti-slavery cause. I think he helped several slaves across the Potomac river. I know he drove one in his carriage, dressed in his wife’s Quaker dress and bonnet. He was a very determined man not afraid of taking risks.

I brought with me to Calif. the soapstone he used in winter time to keep his feet warm on his long drives across the country.

His father was Levi Tate. He [Levi] married Edith Nichols. His home was in Loudoun Co, Va. about 3/4 of a mi. I think from the little village of Philomont to the N.E. His only son William married Priscilla Fenton. They built their home half a mile or less from their father’s home almost directly north. William and Priscilla had no children. William had four sisters, Ann (who died young) Sarah, Mary & Elizabeth. Sarah married Naylor Shoemaker. They were my grandparents. Their children were Levi, Martha, William, Abraham & Edith. Martha married William H. Taylor.

Mary and Elizabeth Tate lived in their father’s home. The last few years of their lives were spent caring for their brother William Tate who lived to an advanced age, in his nineties [sic] I think. I am sorry that I can give thee no dates. Both farms are now owned by Cornelia and Mary T. Shoemaker, descendents of William Tate Shoemaker who married Mary Ann Janney, daughter of Samuel M. Janney, the Quaker historian.

If thee would correspond with Mary T. Shoemaker Lincoln, Loudoun Co. Virginia, I think she could supply the dates thee desires, and probably much more information.

Sincerely Caroline Taylor

1271 Morada Pl. Altadena, Calif.

P.S. Cornelia and Mary Shoemaker are members of Goose Creek Monthly Meeting.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Samuel M. Janney wrote in his Memoirs that William Tate was a companion while traveling across several states to visit other Society of Friends Meetings on religious work: “In the Fourth Month, 1851, accompanied by my friend William Tate, I left home in order to attend the Yearly Meetings of Philadelphia, New York, and Genesee, with some of the meetings composing them.”

Samuel M. Janney was a pre-eminent Quaker leader. He frequently associated with William Tate on Society of Friends’ business. Yet, by the time Janney wrote of this 1851 trip, newspapers picked up the story that William Tate and two others had risked their lives for their anti-slavery beliefs and behaviour. According to family members the Tates helped escaping slaves find freedom in the North, but their actions also endangered their own lives? Here is a Liberator headline, repeated from a Virginia newspaper, the Warrenton Flag: “Supposed Abolitionists Arrested – Elisha Holmes, — Tate, from Goose Creek, Loudoun, and Sales Grist, from Pennsylvania, were arrested on the 20th ult, near Flint Hill, Rappahannock county, Va., on the charge of being engaged in an attempt to carry off slaves.”

A follow up article written in the Baltimore Visitor and copied in the National Anti-Slavery Standard explains what had actually happened:

Transcript: Supposed Abolitionists Arrested. – Three individuals, Elijah Holmes, – Tate, from Goose Creek, Loudon [Loudoun] and Sales [Cyrus] Grist [Griest], from Pennsylvania, were arrested on the 20th instant, near Flint Hall [Hill], Rappahannock county, Va. upon the charge of being engaed in an attempt to carry off slaves. – Boston Atlas.

The Charge of “negro stealing” made against Silas Grist, of Adams county, Pa. and Elijah Holmes, of Loudon [Loudoun] County, Virginia, and others [William Tate], has been contradicted. It seems they were in pursuit of some Virginians who had dragged a family of colored people from Pennsylvania, where they had been actually liberated by their mistress, on removing thither, but, on her death, were claimed by her heirs. The individuals named had gone to Rappahannock county, Virginia, to see after the rights of the colored people, whereupon they were surrounded by a mob of “gentlemen,” of course, and had to be committed to prison for personal safety. Such are the facts, as we have learned them from reliable sources. – Balt. Visiter.

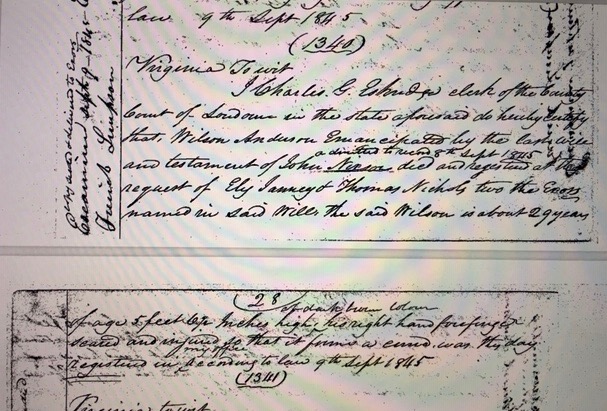

Anti-slavery activities of Lincoln citizens not only risked their personal welfare, but also affected their finances. They constantly attempted to convince neighboring slave-holders to manumit their slaves, and freeing slaves in wills was an occasional outcome. One such case involved local properous landowner John Nixon, a former Quaker. Nixon was convinced, after conversations with Samuel M. Janney, Yardley, Henry and Benjamin Taylor, and others, to manumit his 22 slaves through his will written in June 1845. John Nixon died and his will was probated Sept. 8, 1845. A section of that probated will is shown here which mentions one of the 22 slaves, Wilson Anderson (transcript below):

“Virginia To Wit

I Charles G. Eskridge clerk of the County Court of Loudoun in the state aforesaid do hereby certify that, Wilson Anderson Emancipated by the last will and testament of John Nixon & directed to record 8th Sept 1845 died and registered at the request of Ely Janney & Thomas Nichols two the Executors named in said will the said Wilson is about 29 years of age 5 feet 6 1/2 inches high of dark brown colour, his right hand forefinger scared and injured so that it forms a curve was this day registered in my office according to law 9th Sept 1845″

Coincidentally, this probated will was happening around the same time as William Tate’s apparent arrest in neighboring Rappahannock County.

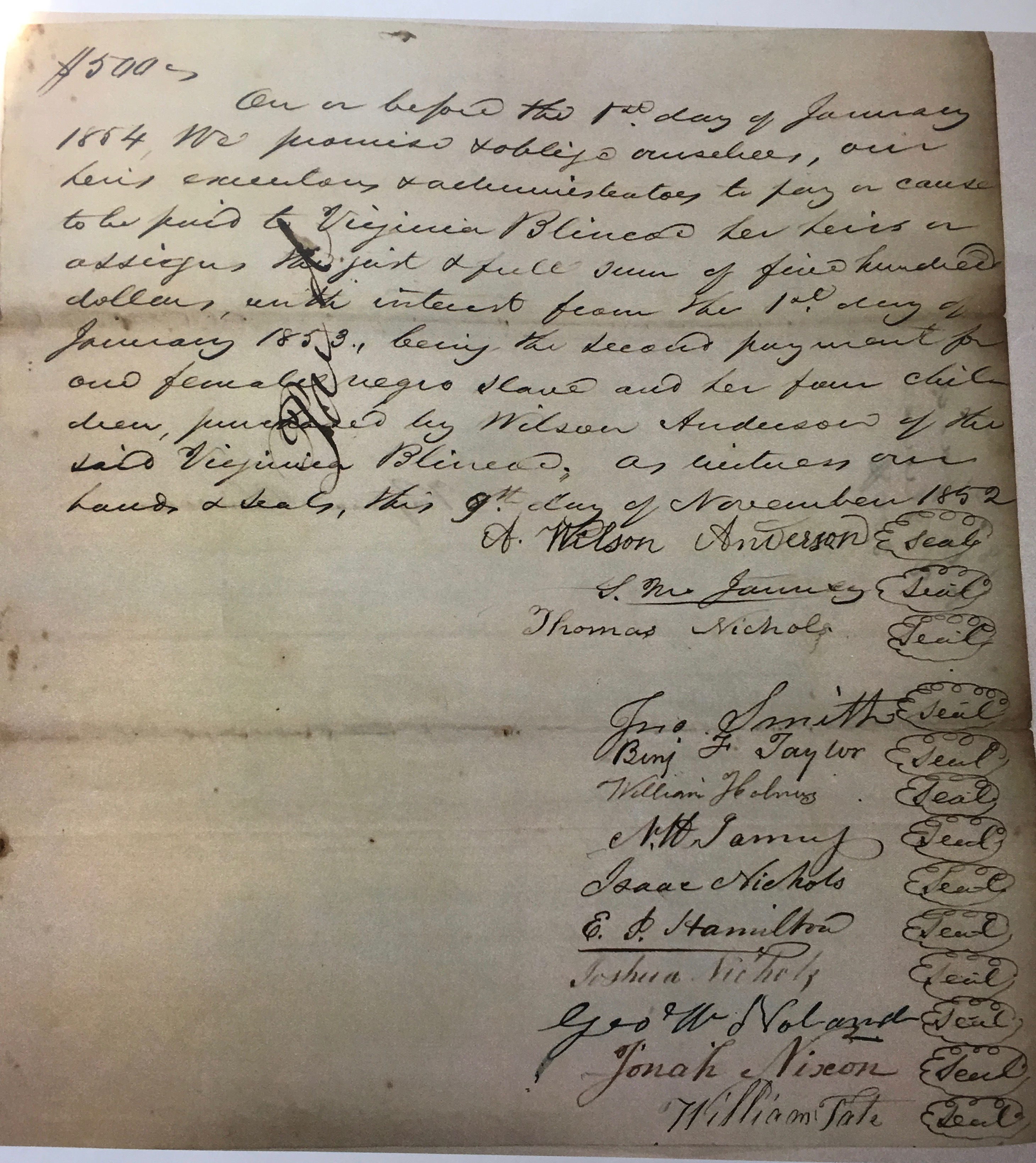

But, what does the will have to do with William Tate? That connection is shown on a later court document involving now freed slave Wilson Anderson. William Tate was named as being in a consortium of Lincoln Quakers and non-Quaker neighbors who bought an enslaved woman and her children, in order to grant the slaves their freedom. Here is the court document from November 9, 1852:

Transcript of the above Loudoun County court document:

$500 ~

On or before the 1st day of January 1854 We promise & oblige ourselves, our heirs executors & administrators to pay or cause to be paid to Virginia Blincoe her heirs or assigns the just & full sum of five hundred dollars, with interest from the 1st day of January 1853, being the second payment for one female negro slave and her four children, purchased by Wilson Anderson of the Said Virginia Blincoe, as witness our hands & seals, this 9th day of November 1852

A. Wilson Anderson (seal)

S.[Samuel] M. Janney (seal)

Thomas Nichols (seal)

Jno [John] Smith (seal)

Benj [Benjamin] F. Taylor (seal)

William Holmes (seal)

N.W. Janney (seal)

Isaac Nichols (seal)

E. P. Hamilton (seal)

Joshua Nichols (seal)

Geo [George] W. Noland

Jonah Nixon (seal)

William Tate (seal)

The enslaved woman and children being bought and freed by these men was the family of Wilson Anderson, manumitted in Nixon’s 1845 will. John Nixon had even left several hundred dollars in his will to pay Thomas Nichols and two other local men to take his former slaves by wagon and settle them in a free state, Ohio.

There are other examples of Quaker families paying to gain the freedom of enslaved men or women; usually the newly freed slaves would ‘work off’ the debt. More information on this will come, but suffice it to say for now: William Tate was an active abolitionist who ‘put his money where his mouth is.’ A short blog post about Tate’s memo book is here.

It was an era when women didn’t want their names in newspapers or in public records, but we know, from the Kitty Payne story, that Priscilla Tate was involved and sympathetic to her husband’s anti-slavery efforts. Hopefully someone has a picture of Priscilla Tate, and we can learn more about her role in the stories being told in Nest of Abolitionists.