Samuel M. Janney was appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Omaha, Nebraska, 1869-1871. His brother and fellow Lincoln, Virginia Quaker, Asa Moore Janney (1802-1887), was appointed Indian Agent at the Nebraska Santee Sioux Reservation.

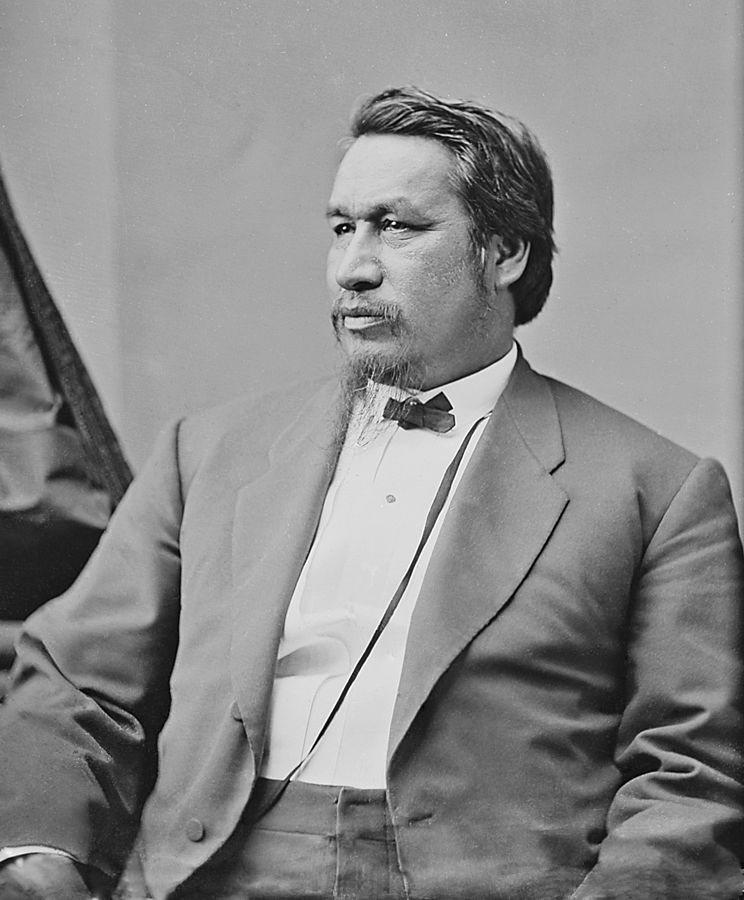

Samuel Janney mentioned in his Memoirs of when he and fellow Quakers first read the letter sent by Seneca born attorney and engineer Ely Samuel Parker, in which Parker requested that Quakers consider work in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Ely Parker was a high ranking and trusted member of President Ulysses S. Grant’s staff. Janney wrote about Parker’s letter:

1869, Third month, 15th. – On the 13th inst. I returned from Baltimore, whither I had gone to meet the Committee on Indian Concerns of our Yearly Meeting. Several Friends from New York, Philadelphia and Ohio, delegated by the representative committees of those Yearly Meetings, were also in attendance.

We met on the 6th inst. to consider a proposition sent us by President Grant, before his inauguration, in relation to the Western Indians. It was conveyed by a letter from E. S. [Ely Samuel] Parker (an Indian), who was one of General Grant’s staff, viz.:

“General Grant, the President-elect, desirous of inaugurating some policy to protect the Indians in their just rights, and enforce integrity in the administration of their affairs, as well as to improve their general condition, and appreciating fully the friendship and interest which your Society has ever maintained in their behalf, directs me to request that you will send to him a list of names, members of your Society, whom your Society will endorse as suitable persons for Indian agents.”

A reminiscence of Samuel Janney’s years as Indian Affairs Superintendent begins in Chapter XX (page 249) of his Memoirs (linked above) and covers the extensive activities of those challenging years – everything from building hospitals to overseeing murder trials. Janney wrote (page 260 of Memoirs) that he, as Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Nebraska, was given the honorary title of “Grandfather” by a council of tribal chiefs; Indian Agent Asa M. Janney was addressed as “Father.” Samuel Janney quoted from his first address to the Omaha tribal chiefs, including Fire Chief, Yellow Smoke and Standing Hawk:

Janney: “Brothers, I do not come here to make you many promises; I wish to make few promises and always to keep them. I know that in times past you have often been wronged by white men, but I feel assured that your Great Father at Washington intends to protect you in your rights, and to do you all the good in his power. He has appointed General E. S. Parker, an Indian chief from the State of New York, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and he has sent your friends out here to be superintendents and agents.”

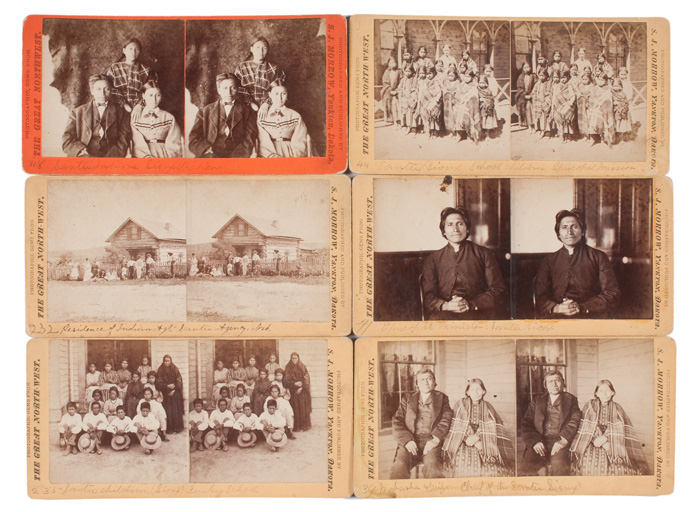

Duane Whipple, historian for Santee Sioux Nation, Nebraska, knows that the history of his tribe is connected to the little Quaker community of Lincoln, Virginia. “The Janneys are remembered as good agents,” he said by phone. “They built a two story grain mill out of red bricks, as well as a saw mill, along the reservation’s Bazille Creek, in order for the Sioux to raise crops, build structures, and have a source of income. They also started a Training School. Asa Moore Janney arranged for blacksmithing to be taught on the reservation.

Unfortunately Bazille Creek kept shifting its course. After several years, the mills had to be abandoned.”

Cornelia, Samuel’s daughter, and Cosmelia, Asa’s daughter – taught at the Training school.

While Asa M. Janney and family lived on the Santee Sioux Reservation, Superintendent Samuel M. Janney’s office was in Omaha, Nebraska. Here is a good overview of Omaha during the era when the Samuel Janney family made that plains town their home. Janney traveled extensively between tribal lands, such as the Winnebago, Pawnee, Sioux, Otoes, and others.

The Santee Sioux Reservation, 174 miles northwest of Omaha, is shown outlined in red on the map below.

President Ulysses Grant trusted the Quakers to be honest and diligent during a time when the Bureau of Indian Affairs was rife with corruption. It is obvious from Samuel Janney’s Memoirs and also from various family letters that the Janneys plunged into a very complicated and difficult bureaucracy when they moved to Nebraska.

Santee Sioux Nation historian Duane Whipple created a timeline of the reservation’s history (shown above in the Santee Sioux brochure) which includes the following:

August 1869 – Santee Reservation Land is established.

October 1869 – Santee agent Samuel M. Janney establishes the first police force of 1 member from each of the 6 bands with the pay of $5 a month.

June 1870 – Tornado wipes out church and school building.

Winter 1870 – Santee Normal Training School is established by A.L. Riggs, with an enrollment of 111 students.

June 1871 – Samuel M. Janney builds 3 story chalkstone sawmill on Bazile Creek so the Santees can grind their own grain into flour.

August 1871 – Santee Normal Training School opens it’s own printing press and begins printing the lapi Oaye [Sioux language].

1873 – Breakout of smallpox epidemic claims 70 Santees’ lives.

1874 – Industrial School opens with an enrollment of 36 pupils and 3 teachers.

A dissertation, published in 1978 at the University College of London, by doctoral candidate Jacqueline Mary Fear, is titled “American Indian Education: the Reservations Schools, 1870-1900.” A link to the entire work can be found here. The complete work is worth reading; it mentions both Samuel M. Janney and Asa Moore Janney.

Historian Jacqueline Mary Fear doesn’t white wash the reality of Native American policy during the decades after America’s Civil War. She wrote of the Quakers, who acted in good faith and tried to honor a native culture which was very little understood. Her dissertation quotes from Harper’s Weekly Magazine:

“There was still no general interest in Indian affairs in

the United States at this time. The “cause” of the Indian never

attracted the same popular attention as that of the Negro,

although reformers would frequently draw parallels between the

problems of the two races. By the mid-1880’s there was more .

widespread concern; in 1886 an article in Harpers Weekly argued

that there was now a powerful public opinion favourable to the

settlement of the Indian question. The author complained that

Congress paid little serious attention to the Indians; he described

how when the House was in the midst of debating the Indian

Appropriation bill “suddenly the oleomargarine tax was sprung

upon the House and the Indians, who have no votes, and

long-delayed justice, and despised rights, and honourable claims,

were swept aside, and the house slipped into a long debate upon

oleomargarine. “ – Harper’s Weekly, June 19, 1886.

Jacqueline Mary Fear concludes: “The principal aim of the Indian schools was the “civilizing” of the children, or, stated more precisely, the inculcation of behaviour and values that were characteristic of American society. Thus the Indians’ response to the schools was necessarily dependent on their attitude to American society and to whites. As the ultimate purpose of the school was the Indians’ assimilation, their view of the society with which they were to merge was crucial to their judgement .and acceptance of the schools.”

Historian Ray H Mattison explains how native American reservations were doled out to various religious denominations in “Indian Missions and Missionaries on the Upper Missouri to 1900,” Nebraska History volumn 38 (1957):

“U. S. Grant in 1869, greatly stimulated the growth of

Indian missions. In accordance with this program, various

churches were allowed to nominate agents for the different

Indian reservations. As a result the Indian Bureau allotted

the Nebraska agencies to the administrative control of the

Society of· Friends (Quakers); the Dakota agencies along

the Missouri, with the exception of those at Standing Rock

and Fort Berthold, to the Episcopal Church; the Montana

agencies, except the Flathead, to the Methodist Church.

The Standing Rock Agency was assigned to the Catholics,

and the Fort Berthold Reservation was placed under the

care of the Congregational Church. This policy permitted

the church, to which the agency was assigned, to control

the education of the Indian children within it and exclude

missions of other faiths. In spite of this policy, however,

the Friends continued to permit both the Episcopal and

American Board churches and schools to function on the

Santee Reserve. The American Board and the Presbyterian

Missions were also allowed to expand alongside the

Episcopal missions on the Sioux reserves assigned the

latter denomination. The Catholics claimed the Indian

Bureau discriminated against them as it allotted them

among the Sioux only the Standing Rock and Fort Totten

agencies.”

Letters back and forth to Nebraska from Lincoln, VA reveal the both exhilarating and exhausting work carried out by the Samuel and Asa Janney families. Everything was something to be learned: native language, mid-west climate, tribal religion and culture, federal bureaucracy…everything.

After two years, Samuel M. Janney submitted his Superintendent of Indian Affairs resignation in the early months of 1871. He wrote about the last months as Indian Bureau Superintendent in his Memoirs, and included the Secretary’s acceptance of his resignation:

WILLIAM H. MACY, Secretary, and WILLIAM DORSEY, Assistant.

Present, eleven members.

“A letter from Samuel M. Janney was read, dated Second month 6th, 1871, enclosing his resignation as Superintendent of the Northern Superintendency of Indians, addressed to the President of the United States, to take effect on the 30th of Ninth month next.

“The subject claimed the deliberate consideration of the committee, and after an expression of much feeling and regret at parting with his services in his present position, his resignation was accepted.

“Barclay White, of New Jersey, was then proposed as a Friend suitable for Superintendent in the place of Samuel M. Janney, which being fully united with, it was concluded to present his name to the President for that station.

“A communication was read, from Barclay White, stating that he was willing to submit to the judgment and wishes of his friends should they feel it right to nominate him to the President.

“The Secretary was directed to forward to Samuel M. Janney and Barclay White copies of the foregoing minute. Signed on our behalf,

WILLIAM H. MACY,

Secretary.”

Janney continues his own personal reminiscence (Memoirs page 286): “In the latter part of the Eighth month, 1871, after my return from a visit to the Winnebago and Omaha Agencies, I was taken sick with intermittent fever, which was thought to be increased in severity by anxiety of mind about Indian affairs. I was mercifully favored to obtain relief, but my strength was much reduced.

The writing of my Annual report to the Government and the care attendant on settling up official business, was too much for my exhausted frame, and near the close of the Ninth month I was taken with the ague.

On the 1st of Tenth month I left Omaha, having delivered to Barclay White the property and funds on hand belonging to the Government. My daughter-in-law, Eliza F. Janney, who had been my chief clerk, was invited by my successor to retain the position. She accepted the offer, and remained at Omaha with her two children.

My wife and daughter accompanied me on the homeward journey. We stopped at West Liberty, Iowa, where we remained about two weeks in order that my strength might be sufficiently restored to travel with safety and comfort. During our stay in that place we attended the meetings of Friends with satisfaction, and on resuming our journey we stopped a few days at Richmond, Indiana, and Waynesville, Ohio, where we attended the meetings of Friends, and, by request, I gave some account of the condition and prospects of the Indians in Nebraska.

On the 27th of Tenth month, 1871, we arrived in Baltimore just in time to attend our Yearly Meeting, and were received by Friends with a hearty welcome. They recognized the propriety of my withdrawal from the Indian service, and we rejoiced together in a cordial reunion of religious fellowship.

During the time of the Yearly Meeting there was a Convention of Delegates from the Yearly Meetings of Philadelphia, New York, Baltimore, Ohio, Indiana and Genesee, which met to consider the work of Indian civilization entrusted to our care.

I made a report in writing to the Convention, and also delivered to a large audience a lecture on the progress of this work in Nebraska and the prospect of successfully carrying out the humane policy of the President in improving the condition of the Indians.“

Thus ended a chapter in Samuel M. Janney’s eventful life. Asa Moore Janney also resigned as Indian agent and returned to the village of Lincoln, Virginia. After decades of effort on the behalf of African Americans, how did the Janneys come to terms with their two years immersed in the native American experience? They were watching that civilization be destroyed; did they themselves interpret the years in that way? Did they feel, ultimately, that they did good, or at least did the best they could under the circumstances? Or, was the experience demoralizing? With the benefit of one hundred fifty years, we can see the endeavor was too immense and fraught to wrap up with well meaning words and good intentions.