Prior to the Civil War Quaker miller Asa Moore Janney (1802-1877) moved his family from Richmond to the community of Goose Creek (now Lincoln) in Loudoun County, Virginia. His life story is told by daughter Lydia Janney Brown on her Nest of Abolitionist page.

Asa Moore Janney’s newly owned mill and farm near Lincoln was known as Forest Mills. In the early months of the war, Janney made special arrangements for families he called “volunteers” or “volunteer families.” What was meant by this label?

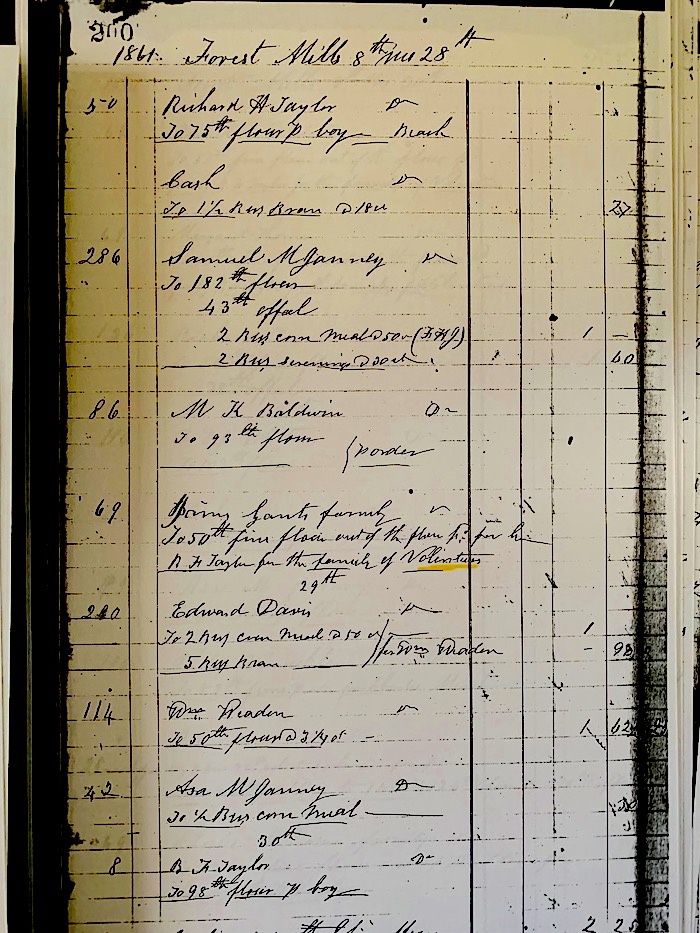

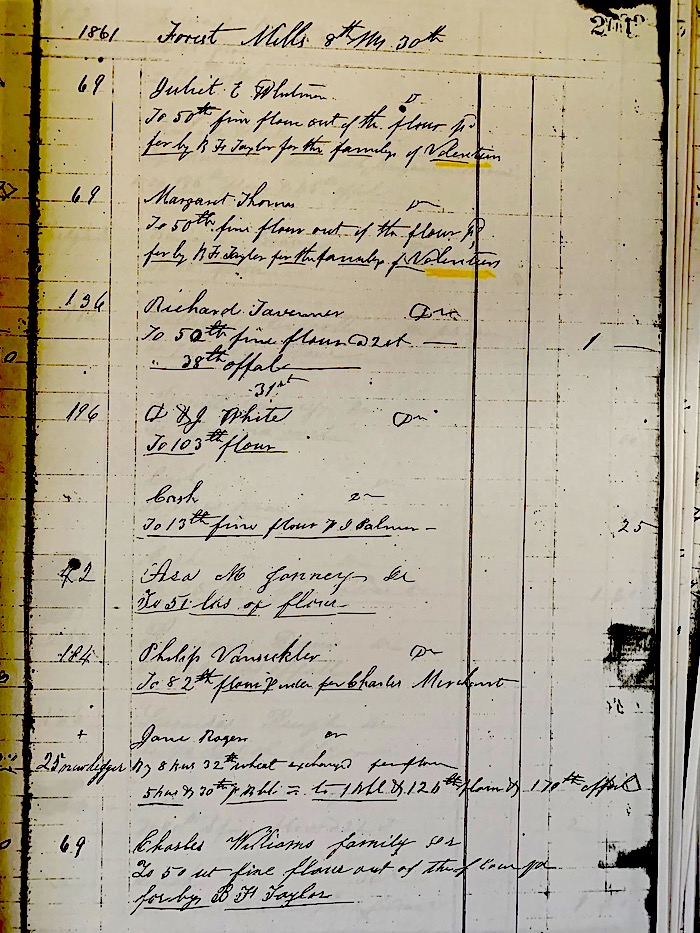

Large ledger books, called Day Books, allowed millers to kept track of their daily business transactions and sales. Several pages from the Forest Mills Day Book, dated during the year 1861, are shown below. Notations show that neighbors and surrounding farmers were buying from the mill or bringing grain to be ground.

B. F. Taylor took on the task of paying for, or perhaps at least occasionally receiving donations, of Forest Mills’ flour to be delivered to various volunteer families. “B.F. Taylor” may have been Benjamin Fenelon Taylor (1830-1910) a disowned Quaker who lived in Loudoun County and would be buried in 1910 in nearby Purcellville’s Baptist cemetery. According to historian John Divine’s 8th Virginia Infantry (H.E. Howard, Inc. 1983), at the outbreak of Civil War, B.F. Taylor enlisted in the Confederate 8th Virginia Regiment. Other 8th Virginia Regiment men include those named Harding, Gants, Whitmore, Whitman, Thomas, and Shipman, all “volunteer” names listed in the mill’s ledger. It is likely the flour, either bought or donated, went to these men’s families.

Asa Moore Janney was a strong Unionist, very much against slavery and the ensuing Civil War. Yet he was also a citizen of the newly formed Confederate states and his Unionist beliefs were unpopular with the majority of fellow Virginians. To keep peace with neighbors fighting and dying for the Confederacy, Janney may have had little choice but to sell or donate flour to infantry families. This practice would continue, one way or another, throughout the entire four years of war: Southern soldiers and cavalrymen – and Federal troops as well – would make raids on Quaker fields, barns, businesses and households.

The notations of “volunteers” (highlighted in yellow and transcribed below the Day Book page image) start appearing on pages by July 1861, three months after war breaks out. Examples are shown below.

paid, John Aldridge, To 150 lb at 2 ct (for the use of the families of the Volunteers)” Forest Mills Day Book copy, private collection.

After September (9 month) 1861 these “Volunteer families” notations are no longer recorded in the Day Book. Why was the practice suspended? It might have to do with B.F. Taylor being listed as “absent due to sickness” by January 1862, according to military records for the 8th VA Regiment recorded by John Divine in his book mentioned in this post. But that is speculation; maybe someone else has a better idea.

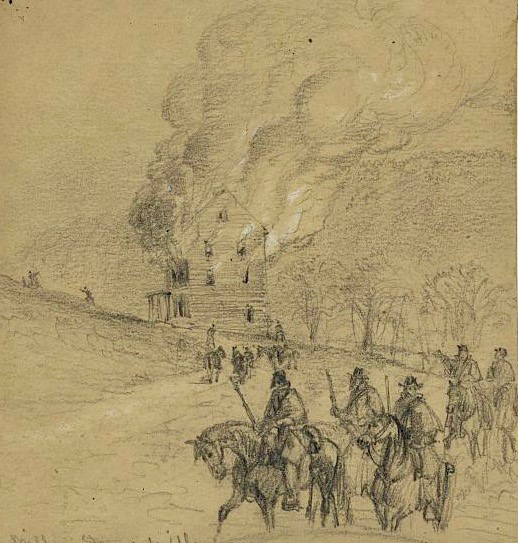

Forest Mill looked similar to the Amos Janney Mill, located thirteen miles away in Waterford, Virginia, and shown in the painting at the top of the page. Like the Amos Janney mill, Asa Moore’s mill was nestled in woods alongside a creek. Forest Mill was burned by Union cavalry men during the Civil War in the autumn 1864 “Burning Raid.” After the war, the United States government allowed loyal Southerners to make claims for property lost to Union troops during the conflict. Many Southern Quakers, having been Union supporters throughout the war, made claims which proved successful.

According to research done at the National Archives by Taylor M. Chamberlin for his book, Where Did They Stand? The May 1861 Vote on Secession In Loudoun County, Virginia, and Post-War Claims against the Government (Waterford Foundation, 2003) Asa Moore Janney made a restitution claim to the U.S. Government for the mill’s burning, requesting $7,536 for the mill’s value.

After the war, Asa Moore Janney rebuilt Forest Mill. He died in 1877 and the mill changed hands. In 1899, 22 years after Janney’s death, the mill burned down again; this time it was not rebuilt. The Alexandria Gazette, May 15, 1899 noted the mill’s destruction:

The beautiful old mill is gone, and an answer to the mystery of “volunteer families” receiving “fine flour” in the early months of war is, perhaps, gone with it.

0 comments on “Civil War “Volunteers” and a Quaker Mill”