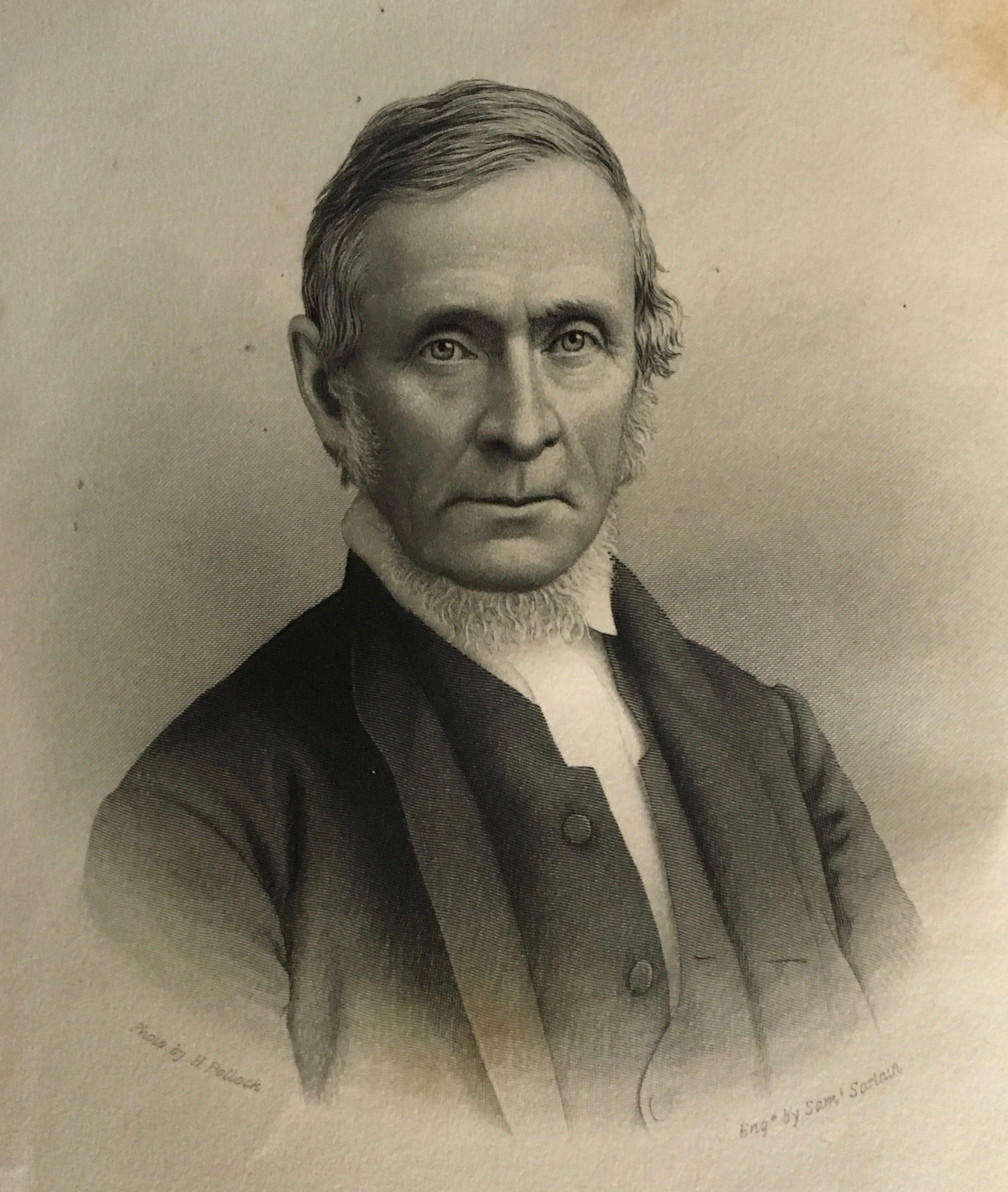

Prominent 19th century Virginia Quaker, Samuel McPherson Janney, had a connection with John Pleasants, the newspaper editor killed in a famous duel. The duel was held in 1846 outside Richmond, Virginia.

In 1845, Samuel M. Janney contacted John Hampden Pleasants, owner and editor of the Richmond Whig. Janney hoped the newspaper would publish some of his anti-slavery essays, including one he called “Yankees in Fairfax.” Janney sought out the Richmond Whig newspaper because it had a wide circulation in the South, and would be read by a population that he felt most needed to hear anti-slavery persuasions.

Decades later writing in his Memoirs, Janney referred to the “Yankees in Fairfax” essay, and quotes a letter he sent at the time to his Philadelphia friend George Truman. Janney wrote that he was grateful to the Friends who donated money to help pay for the essay to be published and distributed as a pamphlet. In the letter, Janney also expressed his views on the “unhallowed scheme” of annexing Texas in order to add slave states to the Union (excerpts below are from pages 91 and 92 of Janney’s Memoirs) :

“The series of essays that attracted most attention, and which incidentally had the most influence on my own career, was entitled “The Yankees in Fairfax County, Virginia,” by a Virginian. It consisted of papers on agriculture, education, and political economy, showing the superiority of free labor over slave labor, in promoting public prosperity, and it was first published in the Richmond Whig with a high commendation from the editor, J. Hampden Pleasants, who was at heart an emancipationist. It was afterwards published in pamphlet form, and a copy of it falling into the hands of Samuel S. Randall, Superintendent of Public Schools in the State of New York, led him to think of coming to Virginia to reside, and ultimately led to an intimate friendship between us, which resulted much to my benefit, as I shall relate hereafter.

The following letter I wrote to my friend, George Truman, of Philadelphia.

SPRINGDALE, 2d mo. 10th, 1845

“Dear Friend: – I have to acknowledge the receipt of thy kind letter, and can assure thee I feel grateful for the confidence reposed in me by the Friends who have subscribed for the publication of my letters against slavery. I am particularly pleased that a way has been opened for some to contribute who are not engaged in the effort now being made in this cause in the free States. It shows that Friends who have stood aloof from that movement may nevertheless feel a warm interest in the cause, and a willingness to assist when they can see the way clear to do it. This will promote charitable feelings among us, and may prevent the spreading of that dividing and desolating spirit which has crept into some of our meetings in the Western States. I do greatly desire that brotherly love may continue, and that we all may be concerned to put the light upon the candlestick that it may be seen of all.

“If something be not done soon towards the removal of the burdens by which the poor oppressed slaves are borne down to the earth, I believe an awful retribution awaits this guilty land, and when national calamities shall come upon us, the innocent will have to suffer with the guilty. But when we examine this subject closely, I fear that few of us are entirely innocent of giving countenance in some way to a system of oppression and cruelty that has seldom been equalled in any age. Even in the free States the unhallowed scheme of annexing Texas, which would add more slave States to the Union, and consequently would increase the domestic slave trade, has found many supporters. This astonishing infatuation must arise from interested motives on the part of political leaders, whose eyes are blinded by the god of this world.

Thy affectionate friend,

SAMUEL M. JANNEY.”

Janney hoped his anti-slavery essays, including “Yankees in Fairfax,” would appear in the Richmond Whig in weekly installments.

John Hampden Pleasants (1797 – 1846) owned the only Richmond newspaper that would publish such controversial essays. His Richmond Whig championed the Whig political party. A precursor to the Republican party, Whigs generally supported the eventual ending of slavery, though there were many opinions on how to achieve that goal. Pleasants professed to be anti-slavery, but his editorials meandered on all sides of the issue. He publicly expressed through his editorial columns that he was against slavery not because it was detrimental to blacks, but because it harmed white citizens. Needless to say, his was not a leading voice in the cause of emancipation, but Samuel M. Janney had few options if he wanted to publish anti-slavery writing in a southern newspaper, thereby reaching a large number of pro-slavery readers.

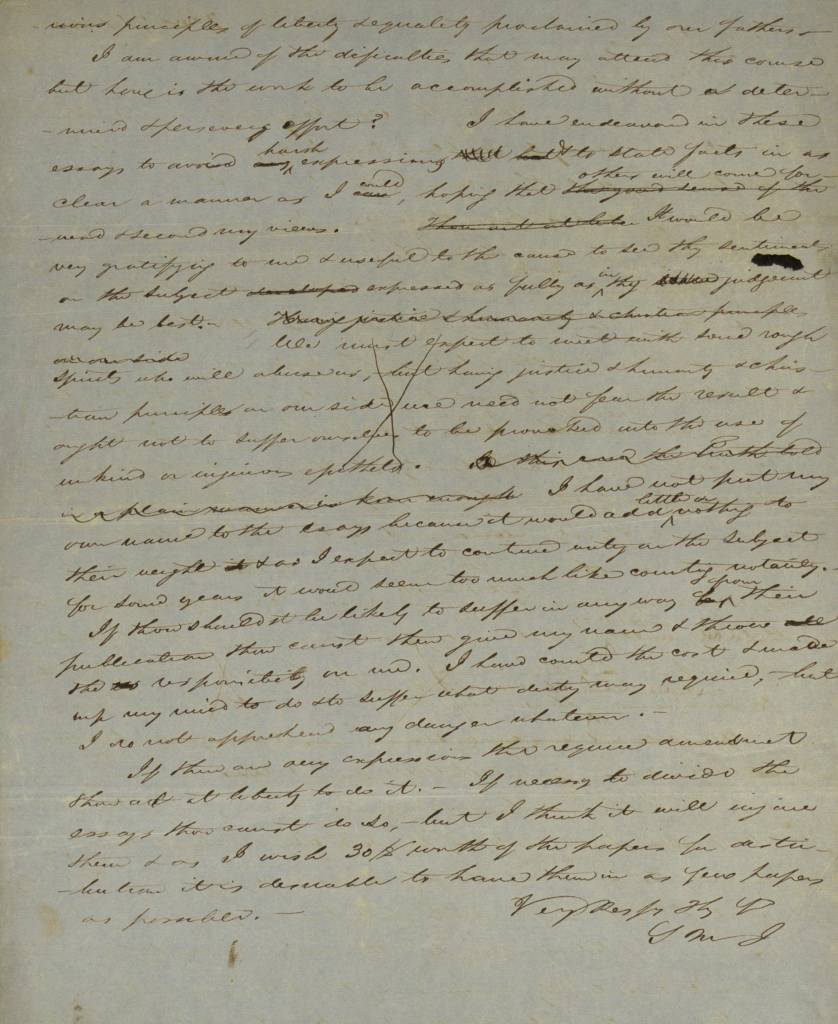

As a young man, Samuel M. Janney had published a series of anti-slavery essays in the Alexandria (Virginia) Gazette in April-May 1827. Those essays may be read here. He continued to use many of those same arguments against slavery throughout his life. Now, he entered in correspondence with John H. Pleasants about publishing a similar series in the Richmond Whig. A letter written from Janney to the editor on July 7, 1845 expressed hopes for his essays (transcript below image):

7 mo 7 1845. J H Pleasants, Repd friend, My brother Asa having informed me that thou art now ready to publish my series of essays on slavery, & that the copy sent thee cannot be found, I have prepared another copy which I herewith send. My heart is so deeply interested in this question that I have (with the assistance of a friend) transcribed them this third time without thinking it a hardship, & I earnestly desire that this little effort for the good of my country & the relief of the oppressed may be blessed by author of all Good at least so far as to awaken the attention of minds abler than mine to plead this great cause. I feel as though I could hardly let this opportunity pass without remarking to thee, that I hope much from thy vigorous and independent spirit in advocating awareness that are fraught with the importance to the welfare of our state, & may I not say to the progress of our race. It appears to me that the present is a more propitious time than we have had for some years past, the public attention has been awaked by the [dissentions] in church & state produced by this question, the discussion now going on in Kentucky must be felt in Va, and the full tide of public sentiment in favour of liberty throughout the civilized world is rushing onward & must eventually sweep away the bulwarks of slavery. May we [then] stand up & dare to acknowledge the glorious principles of liberty & equality proclaimed by our fathers. I am aware of the difficulties that may attend this course but how is the work to be accomplished without a determined & persevering effort? I have endeavored in these essays to avoid harsh expression & to state facts in as clear a manner as I could, hoping that others will come forward & second my views. It would be very gratifying to me & useful to the cause to see thy sentiments on the subject expressed as fully as in thy judgement may be best. I have not put my own name to the essays because it would add little or nothing to their weight & as I expect to continue writing on the subject for some years it would seem too much like [courting ???]. If thou shouldst be likely to suffer in any way from their publication thou canst then give my name & throw the responsibility on me. I have counted the cost & made up my mind to do & to suffer what duty may require, but I do no apprehend any danger whatever. If are any expressions that require amendment thou art at liberty to do it. If necessary to divide the essays thou canst do so, but I think it will injure them & as I wish 30$ worth of the papers for distribution it is desirable to have them in as few papers as possible. Very respy thy fd, S M J-

John Pleasants began publishing Janney’s anti-slavery series. However, the editor questioned one essay’s assertion that emmancipated slaves should have the right to remain in Virginia. (State law forced former enslaved men and women to leave Virginia within a year’s time.) Samuel M. Janney wrote to Pleasants and his junior editor addressing this concern, on August 26th, 1845:

Springdale 8 mo. 26th 1845. J. H. Pleasants & R. H. Gallaher, Respd. friends, I have just recd a letter from my brother Asa in relation to the series of essays on Slavery which you commenced publishing some weeks ago. He says you think “One of my views will not do for Va, which is that the emancipated blacks are to remain amongst us.”–& that you propose to strike it out or alter it. He writes to know my sentiments on the subject which I [prepare giving] in as few words as I can. I have looked over the [remaining 3] to see what changes can be made to suit your views without violating my own consistency & sense of right & I confess I cannot see how that feature can be left out for it runs through the whole & is a prominent part of my plan. In fact I consider it (after reflection for many years) the only feasible plan, but still I wish to hold myself open to conviction & if you or any of your correspondents can shew a better way I shall heartily rejoice. Almost any thing is better than the state we are now in & I am fully persuaded it cannot be very materially improved without the extinction of slavery.

Within a few weeks past I have conversed with a number of intelligent northern men settled in Fairfax Co who say our waste lands would soon fill up if slavery were abolished & the rise in Real Estate would pay for all the slaves liberated. They think the blacks by good treatment would make very good labourers when employed on [?] & there is no need of expelling them for we shall be in want of labourers when Virginia awakes to the spirit of In the neighbourhood where those northern people are settled there is already a striking improvement & the price of land has doubled within 4 years. I am writing a [series] of essays entitled the “Yankees in Fairfax” relating to the process employed for renovating the soil, the effects of industry skill & intelligence, the [?] of Virg’a [declare] & the means of her empowerment, with others reflections [illegible] to you. With respect to the 3 essays you now have, you can judge better than I can what is right & proper for you to do, but I should suppose a correspondent might be allowed in this free country to speak his own sentiment without the editor being held responsible for them. If you dissent from [them] I have no objection to your saying so & if your correspondents undertake to [repeat them] & you give and [?] to reply I think I can stand my ground. If they lose their temper I am determined to maintain mine. My sentiments with regard to [emancipation] on the soil have already been published within a year past in the Alexa. Gazette & the Balt. Visitor & I do not feel willing to retreat until convinced of error, but if you think the essays can be altered to suit your views without rendering me inconsistent I should be pleased to hear of the alterations proposed. V. K. yr F S M J

A few weeks later, Janney wrote again. He promoted his new essay, “Yankees in Fairfax,” which tackling the subject of slavery from a different angle: farms worked by enslaved labor were both less productive and more expensive to run than farms worked by free labor.

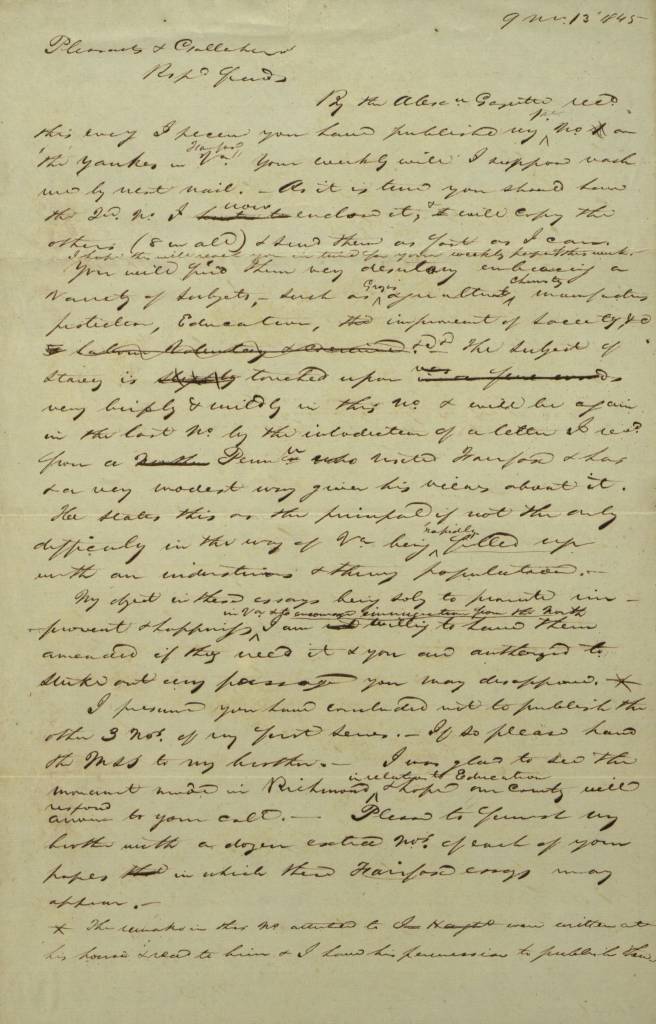

Janney’s entire “Yankees in Fairfax” essay can be read here. After receiving Janney’s September 13, 1845 letter, Pleasants began publishing installments of “Yankees in Fairfax” in the Richmond Whig. Below is a letter Janney wrote once the series began appearing in print. The plan was to print it over a series of weeks. However, for John H. Pleasants, time was running out.

Transcript:

9 mo 13 1845. Pleasants & Gallaher, Repd friends, By the Alexa. Gazette recd. this eveg I perceive you have published my 1st no. of “the Yankees in Fairfax Va.” Your weekly will I suppose reach me by next mail. As it is time you should have the 2nd. no. I now enclose it, & will copy the others (8 in all) & send them as fast as I can. I hope they will reach you in time for your weekly, hopefully this week. You will find them very desultory embracing a variety of subjects, such as Grg’s agriculture, charity, manufacturers protection, Education, improvement of society &c &c & the subject of slavery is touched upon very briskly & mildly in this no. & will be again in the last no. by the introduction of a letter I rec’d from a Penna who visited Fairfax & has in a very modest way given his views about it. He sees this as the principal if not the only difficulty in the way of Va. being rapidly filled up with an industrious & strong population. My object in these essays being solely to promote improvement & happiness in Va. & to encourage immigration from the north I am willing to have them amended if they need it & you are authorized to strike out every passage you may disapprove. * The remarks in this no. attendant to Jno. Hampden were written at his house & read to him & I have his permission to publish them. * I presume you have concluded not to publish the other 3 nos. of my first series. If so please hand the MSS to my brother. I was glad to see the movement made in Richmond in relation to Education & hope our county will respond to your call. Please to furnish my brother with a dozen extra nos. of each of your papers in which these Fairfax essays may appear.”

It was brave of John Hampden Pleasants to put any anti-slavery essays before his Southern readers. His world was far away from the quiet pews of a Loudoun County Quaker meetinghouse. Pleasants had, for years, written mild opinions in support of gradual emancipation. The fact that he would print Janney’s series of logical arguments against the whole slavery system was seen by many as an attack on the entire social order. Southern emotions ran hot on the subject; it was no surprise the topic would be used to sell newspapers. Pleasants became caught up in a public and acrimonious battle with a rival newspaper’s editor, Thomas Ritchie, Jr.

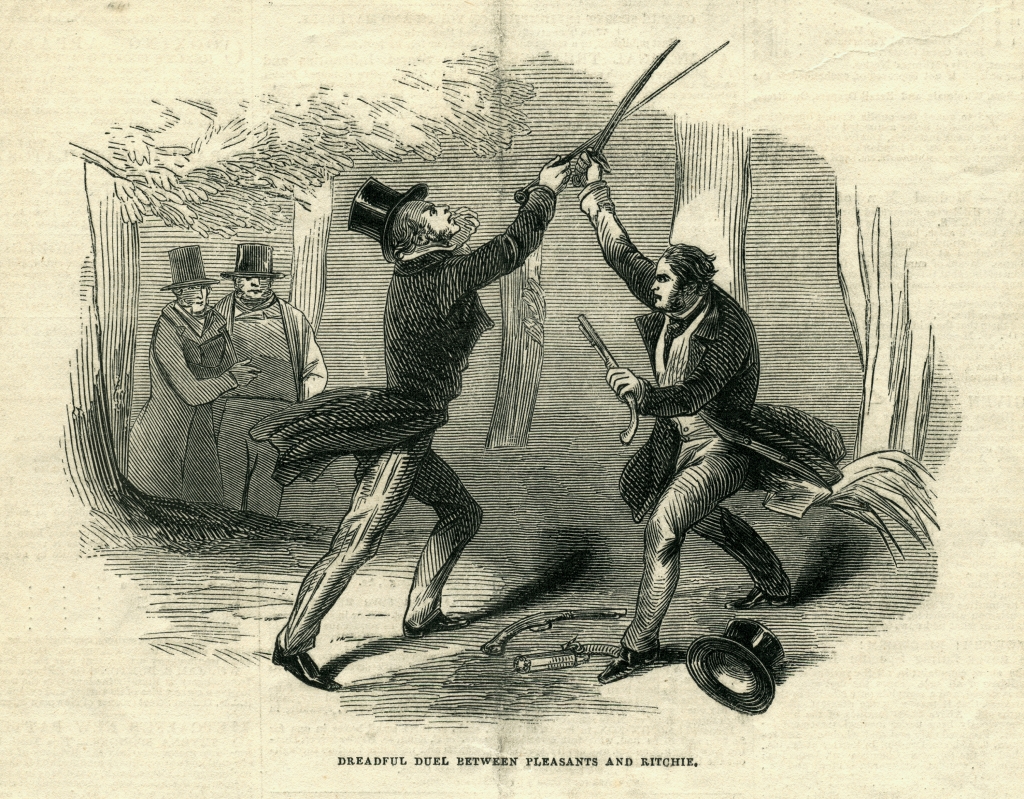

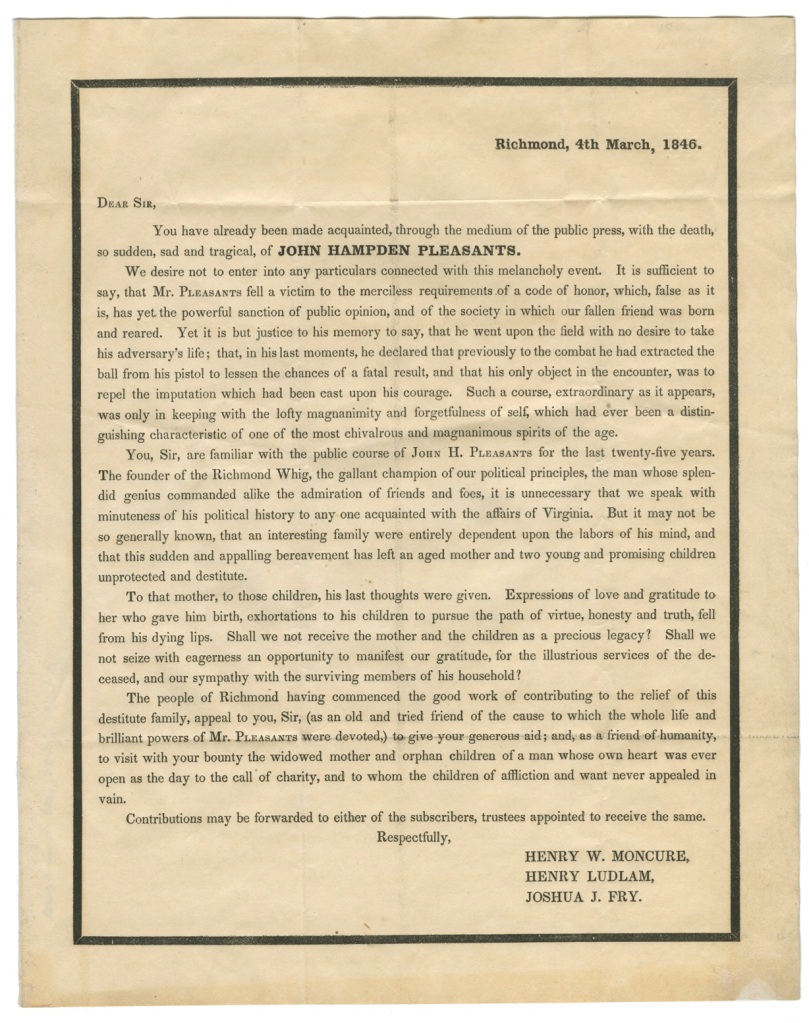

Thomas Ritchie, Jr. was a 26 year old son of the founder of Virginia’s most widely read newspaper, the Richmond Enquirer. Ritchie, Jr. served as an editor on the newspaper alongside his father. The Enquirer vociferously supported slavery and the extension of slavery into western states. For years, the Richmond editors sparred both in person and in print on the topic of politics and slavery. In autumn of 1845 the Enquirer editor wrote an column calling Pleasants an “abolitionist” and “a coward.” In the 19th century South – and in the North, for that matter – to be called an abolitionist was a tremendous slur. But it was the “coward” aspersion that seemed to most enrage John H. Pleasants. For the sake of his slighted honor he challenged Ritchie, Jr. to a duel. Ritchie, Jr. took up the challenge (lest he be considered a “coward”) and the resulting encounter led to Ritchie besting Pleasants in the duel, shooting him four times and finally mortally wounding him with a sword. Friends of Pleasants claimed he had gone to the duel site with blanks in his pistol, only intending to frighten Ritchie into changing his behavior.

The duel received national attention, and Thomas Ritchie, Jr. was tried for the murder of John Hampden Pleasants. He was acquitted of the charge; dueling was still considered a legal and honorable, even gentlemanly way to settle certain public differences. A copy of the Enquirer editorial column that led to the duel, plus a transcript of the ensuing murder trial was published in booklet form. It can be found here.

Did Samuel M. Janney’s anti-slavery essays add fuel to the fire of vitriol and hate that flared between the two newspaper rivals? Was it a coincidence that Janney’s essays were being published in the Richmond Whig even as the rival Enquirer decried Whig editor John H. Pleasants as being an “abolitionist” during the days leading to the fatal duel? Samuel Janney remained publicly silent on this whole tragic episode; it was one more prelude to the coming war.

0 comments on “The Duel”