“The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln” published by Rutgers University Press, contains eight volumes of letters, speeches and memos by Lincoln from over the course of his public life. Quakers occasionally figured in Lincoln’s writing. One such example is January 4, 1855 when Lincoln drafted a speech to the American Colonization Society. Colonization Societies were popular within the anti-slavery movement during the early to mid-1800’s. A good overview of the movement is found at the Abraham Lincoln Historical Society.

This draft transcript of a speech by the future president on the topic of colonization is from Lincoln’s Collected Works, Volume II, pages 298-299. It is insightful to see how Lincoln used a timeline to cover the history of slavery. He held up Quakers as examples of individuals who took a moral stance against slavery, abolishing the practice within their denomination:

“Outline for Speech to the Colonization Society“

“1434 – A portaguse [sic] captain, on the coast of Guinea seizes a few Affrican lads, and sells them in the South of Spain.

“1501 -2-3 Slaves are carried from Africa to the Spanish colonies in America.

“1516-17 Charles 5th of Spain gives encouragement to the African Slave trade.

“1562- John Hawkins carries slaves to the British West Indies.

“1620 – A dut[c]h ship carries a cargo of African slaves to Virginia.

“1626 – Slaves introduced into New York.

“1630 to 41 – Slaves introduced into Massachusettes

“1776 – The period of our Revolution, there were about 600,000 slaves in the colonies; and there are now in the U.S. about 3 1/2 millions.

“Soto, the catholic confessor of Charles 5, opposed Slavery and the Slave trade from the beginning; and, in 1543, procured from the King some amelioration of its rigors.

“The American colonies, from the beginning, appealed to the British crown, against the Slave trade; but without success.

“1727 – Quakers begin to agitate for the abolition of Slavery within their own denomination

“1751 – Quakers succeed in abolishing Slavery within their own denomination.

“1787 – Congress, under the confederation, passes an Ordinance forbidding Slavery to go to the North Western Territory.

“1776 to 1800 – Slavery abolished in all the States North of Maryland and Virginia.

“1808 – Congress, under the constitution, abolishes the Slave trade, and declares it piracy.

“1816 – Colonization Society is organized – its direct object – history – and present prospects of success. Its colateral objects – Suppression of Slave trade – commerce – civiization and religion.

“Objects of this meeting.”

“All the while – Individual conscience at work.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Loudoun County, Virginia’s Manumission and Colonization Society included membership of several Goose Creek Meeting Quakers. Donations to Colonization Societies were used to pay costs incurred sending formerly enslaved men and women – who voluntarily wanted to emigrate – to the African nation of Liberia (founded in 1822.)

American Colonization Societies started in 1816 and were active for decades. Similar organizations were Manumission and Emigration Societies. Yardley Taylor was President of the “Manumission and Emigration Society of Loudoun County” during the 1820’s; his newspaper letter supporting the Society’s cause is here. Taylor eventually supported raising money to transport manumitted former slaves to Haiti – Haiti being a closer nation and ruled by black citizens. However, the majority of colonization efforts were focused on Liberia.

Emigration was often less than successful. Loudoun County’s Thomas Balch Library’s Black History Committee has uncovered local colonization history. Letters from two Loudoun County emigrants detail many of the challenges faced in Liberia, including malaria, homesickness, and political unrest.

For all these reasons, the colonization enterprise eventually became untenable. In addition, re-locating people abroad was very expensive. By 1867, the Society had only settled around 13,000 former emigrants in Liberia.

The majority of Blacks, ultimately, didn’t want to resettle in Africa. America was their home and they demanded their right to citizenry. Even so, Lincoln clung to the idea of colonization after most had given up on the effort as misguided.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If Abraham Lincoln supported colonization in the hope that it might both deter war and correct the moral sin of slavery, his hopes were dashed. Yet Lincoln continued to push financing for emigration of freedmen and women to Liberia as late as 1864. It was an effort he had shared with many anti-slavery Americans. However, the majority of leaders in the abolitionist movement were increasingly against the controversial, expensive, and ultimately unpopular effort. By the mid-19th century, Quakers of Goose Creek Meeting seem to have given up on colonization.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-slavery beliefs remained a strong connection between Quakers and Abraham Lincoln. During the war years of 1861-1865, Lincoln received letters of support from many Americans, and specifically many Quakers, thrilled with his announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation. Quaker Caleb Russell – formerly of Goose Creek Meeting – and Sally Fenton wrote the President and received a reply.

Lincoln also had occasional White House visits from Quakers. One of the most meaningful of those visits was with Quaker preacher Eliza Kirkbride Paul Gurney (1801-1881).

Lincoln met with Gurney in the White House, and the two subsequently corresponded. Lincoln’s September 4, 1864 letter to Eliza Gurney reveals his sensitivity to Quakers’ moral conflicts during the war, when the issue of slavery was being settled. Part of his letter states: “Your people – the Friends – have had, and are having, a very great trial. On principle, and faith, opposed to both war and oppression, they can only practically oppose oppression by war. In this hard dilemma, some have chosen one horn and some the other. For those appealing to me on conscientious grounds, I have done, and shall do, the best I could and can, in my own conscience, under my oath to the law. That you believe this I doubt not; and believing it, I shall receive, for our country and myself, your earnest prayers to our Father in Heaven. Your sincere friend, A. Lincoln”

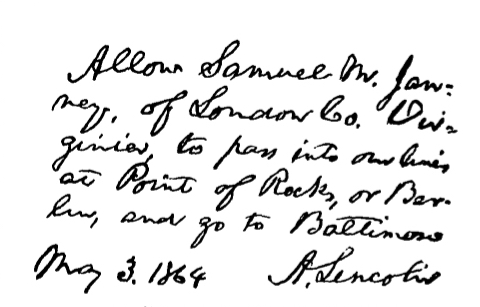

War memos, including those sent by Union General Ulysses S. Grant, show that Lincoln was aware of Unionist Quakers living in Loudoun County, Virginia. Information on the war memos can be read here. Eliza Janney Rawson, writing in 1899 about her former father-in-law Quaker Samuel M. Janney, published a photostat of the travel pass issued to Janney by President Lincoln on May 3, 1864 (shown below, right) :

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In 1866, Quakers in Loudoun County, Virginia changed their village name from “Goose Creek” to “Lincoln” in honor of the martyred President. It was a fitting tribute. Like Lincoln, many Quakers had supported colonization in a bid to end slavery without resorting to violence to achieve the goal. Eventually the nation was forced onto a different path. As Lincoln wrote to Eliza Gurney, on September 4, 1864: “On principle, and faith, opposed to both war and oppression... In this hard dilemma, some have chosen one horn and some the other.”

The Quaker path was one of pacifism and persuasion. The other path led to war but, eventually, to emancipation. Yet who is to say that both paths didn’t lead in the same direction, setting our nation’s course toward a better future?

0 comments on “Abraham Lincoln, Colonization and Loudoun County Quakers”