Lucretia Mott was a Philadephia Quaker and one of the nation’s most promenant abolitionists. She was also an early feminist which, for the era, was perhaps an even more controversial position than her abolitionism. There are many good books, articles and sources of information about this remarkable woman; two brief biographical sketches are the Mott wikipedia biography and this one from the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

The official Goose Creek Meeting minute’s dry mention of Lucretia Mott’s visit belies the nature of this woman’s ministerial and personal reputation. She was known to be a persuasive speaker, as well as personally courageous and confident. By nature of her temperament she took a bolder position on the moral and ethical issue of slavery than did most of her fellow Quakers, opposing slavery by any peaceful means possible. She, in common with the great majority of Quakers, were pacifist, and for that one reason alone would not condone violent anti-slavery actions. And yet in October 1859, seventeen years after her visit to Goose Creek Meeting, it was Lucretia Mott who opened her family home to Mary Brown, wife of radical abolitionist John Brown and mother of a son killed during the 1856 ‘Bloody Kansas’ raids, as well as two sons killed during their father’s failed 1859 raid at Harpers Ferry. Mary Brown stayed with the Motts during John Brown’s imprisonment, trial and finally, execution.

Mott’s political radicalism made her one of the best known women in the United States. She ran an Underground Railroad site out of her family’s own Philadelphia home. She was a friend of Frederick Douglass, William Still, and other black abolitionists. She regularly turned up to sit by the side of escaped enslaved men and women who found themselves in Northern courtrooms, seeking protection from Southern masters. Lucretia Mott stood barely 5 feet tall and weighed less than 100 pounds, but was a giant in the decades long struggle of abolitionism. Her presence in the Goose Creek Meetinghouse in Lincoln November 1842 must have been electrifying for the men and women of the village, many of whom shared her ministerial convictions and abolitionist goals, and several – such as William Tate – who shared her zealous temperament.

Lincoln’s educator and anti-slavery activist Samuel M. Janney was strongly influenced by Lucretia Mott. Dr. A. Glenn Crothers wrote about Janney’s reaction to Lucretial Mott in a 2006-2007 article for the Southern Friend: Journal of the North Carolina Friends Historical Society, including the following excerpt:

The instigation for Janney’s new [anti-slavery] activism was the 1842 visit of abolitionist Quaker Lucretia Mott to the yearly meeting. Janney reported that

before she spoke “there was much apprehension felt by many friends

about her abolition views.” However, after “she delivered one of the

greatest discourses” Janney had “ever heard,” he and Baltimore Friends

were convinced “that she was on the right ground in her ministry.”

For Janney, Mott’s visit was a revelation. In the wake of her departure

he began corresponding with antislavery allies throughout the country

and published a series of articles in Alexandria, Richmond, and

Baltimore newspapers documenting the debilitating impact of slavery

on the economic, educational, and cultural life of Virginia. By 1849

he had attracted so much attention that Loudoun County slaveholders

had him arrested for inciting slave unrest.

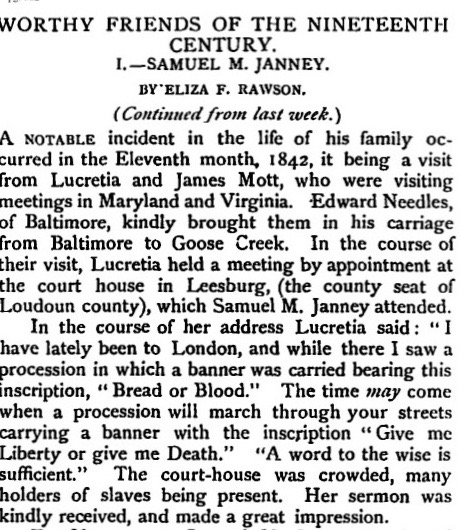

In 1899, Eliza Janney Rawson wrote about the Mott visit to Lincoln in this column for the Friends Intelligencer:

After the Civil War ended in April 1865, Lucretia Mott’s work on behalf of injustice didn’t stop; she continued to provide a moral compass on freedmen’s and women’s rights. The goal of women’s suffrage was not realized in Mott’s lifetime.

Samuel M. Janney maintained a close relationship with James and Lucretia Mott as well. This brief clip from a Virginia newspaper (below), the Richmond Dispatch, of May 1872, is an example of Janney and Mott’s joint efforts. The Dispatch‘s notice takes a surprising conciliatory tone, considering how for decades the anti-slavery work of Quakers had been written of in the Southern press with extreme and hostile criticism.

James and Lucretia Mott Life and Letters written in 1884 by Anna Davis Hallowell, Mott’s grand-daughter, can be read on Google books, online.